a writing schedule is not a writing practice

and other lessons i've learned along the way

astrology for writers is a labor-intensive, exclusively reader-supported publication. if you enjoy getting this newsletter in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

I sat down to return to the Writing With the Moon series yesterday, but this came out instead. I hope that’s alright.

Please note that, after years of offering this reading, I have changed the name of my current primary offering from My Best Writing Routine to My Best Writing Practice. To me, a routine and a practice are very similar in meaning, but as my use of those words is also grounded in a decidedly anti-capitalist philosophy of art-making, I want to level-set clients’ expectations. More on this subject, generally, below.

A brief content warning for non-graphic references to mental health events and sexual assault.

A not-insignificant number of my clients who come to me for help with their writing routines are looking for a prescription that will fix their perceived not-writing. They expect, or perhaps just want, me to provide a schedule, or deadlines, or the right Things To Do that will unblock them and automatically create more space in their life. What if I wrote on Tuesdays instead of Mondays? At night instead of during the day? Word count goals don’t work for me — what about a different kind of deadline?

I often worry that (in spite of the testimonials) folks leave their readings with me profoundly disappointed. I’m not a mind-reader; I can’t just tell someone when to fit writing into their life. But I especially cannot do this when, through both chart interpretation and questions of my own, the issue at the core of the writer’s frustration or anxiety is not actually one of scheduling, but rather, the balance of creative Input and Output. Their own unreasonably painful expectations of their work. Their own relationship to creativity.

The mindset of what writing is, or what, precisely, “counts.”

The decidedly capitalist conflation of an artistic practice with a schedule of production.

Because let me tell you. Almost every person who sits in my client chair is exhausted, fatigued, or burned out. And simultaneously wondering why they don’t have the energy to write 1000 words a day.

I believe that Creativity is a force we as artists are in relationship with. Call her the Muse; call her a goddess; call her something else. But she (to me, Creativity is a she) is a force that works independent of us and through us and in collaboration with us. One of the hallmarks of humanity is — as Diana Rose Harper so beautifully said in our recent interview (fittingly titled “ecosystems, not empires”) — the sheer diversity of creative modalities that has emerged from our species. Song and dance and visual art and sculpture and oral storytelling and drama and comedy and writing and books and drag and jewelry and fashion and food and perfume and and and.

Humans collaborate with Creativity — not just in the so-called Fine Arts — every single day. We play with language when we make jokes; we play with Aesthetic every time we dress ourselves or do our hair and makeup.

The question is, how conscious are we of our ongoing collaboration with Creativity? Do you only feel creative when you are “productive” — which is to say, when you have produced something that can be sold?

That conflation of creativity with productivity is anathema to the soul.

Where is the romance? The relationship of it all? Where is inviting Creativity to come with you on your daily walk, or out with you in the garden? Where is the respect for that time spent with her?

Only valuing her when she coughs up something worth selling does not a healthy relationship make.

A writing schedule is not a writing practice.

What is a practice? A routine or a ritual?

It is something you are committed to. Dedicated to. Something you show up to.

That does not mean doing it every day — or even multiple days a week.

Lighting a candle for the New Moon (every two weeks) is a practice.

Going to church on Sundays, or reading my week ahead newsletter on Sundays!, is a practice.

Having a monthly date night with your partner(s) is a practice.

Taking a summer trip to the same place, or at the same time, with loved ones every year is a practice.

The frequency or duration is not the point. It’s the intentionality, the dedicated time that nourishes the soul in sacred ritual. X is what I do for Y.

(Consider: these are also things you may well skip doing if you are sick, or taking care of a loved one in need, or are having to work extra hours because money is tight, or just feel burned out and need a break.)

The thing about practices is that they are, inevitably, informed and affected by other parts of life.

The thing about practices is that they get to be fluid in response to our life year over year, month over month, day over day.

How many of you are judging yourself for a writing schedule that only worked when you were in college, or before your kids were born?

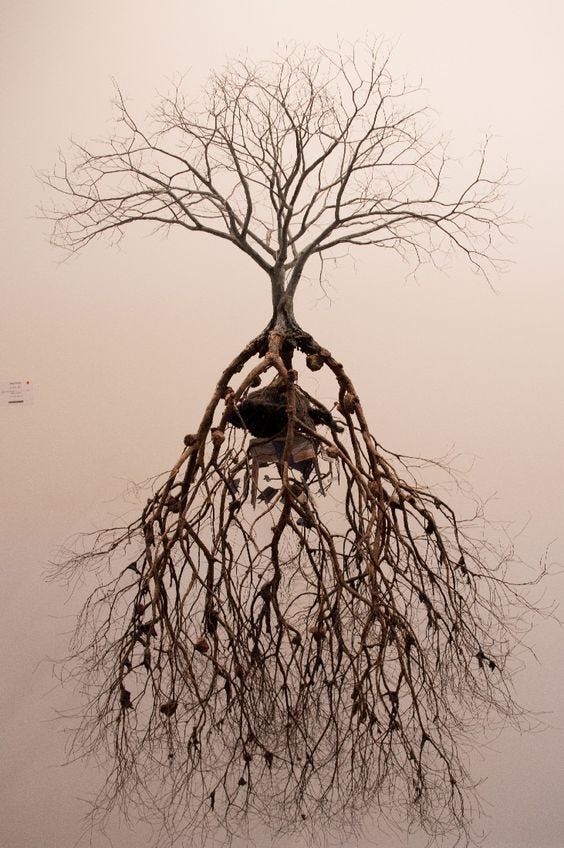

You have changed. Your relationship to Creativity has also changed: composted and deepened its roots over time. Why wouldn’t the nature of your writing?

I did not write for years while in my PhD program. Or rather, I did write. Dozens and dozens of journals. Research papers. Other papers I wrote solely to be presented at conferences (those had to do with fairy tales and fantasy literature, of course). Syllabi. Writing assignments for my students.

I wrote every day. I just didn’t write work with the intent to publish. The work wasn’t publishable — which is, by many people’s internalized capitalist standards, the only kind of “writing” that “counts.”

In those years, I was going through that unique spiritual, existential crisis that is being married to a man while realizing you’re a lesbian, that, for me, was compounded by being a Believer in a faith that was profoundly homophobic, conservative, and ultimately hostile to the idea of freewill. My mental health collapsed; for a time, I was suicidal. For a time, after leaving my ex-husband, I was unhoused and dependent on the couches and goodwill of friends to keep me sheltered — the first time I would choose homelessness in order to get out of an unlivable partnership, but not the last.

The only thing I wrote for myself were those journals. And in the years after those crisis events, where I was recovering and rebuilding my life from the rubble (burned out is an insufficient term), I also did not write — except those journals, which were only ever for myself and will never see the light of day. I opened an LGBTQIA+ focused lingerie boutique and wrote an active blog for it, but I did not write for myself. I could not expose myself yet. I was too tender; too new. In opening Bluestockings (my store), I was being creative, but creating a business did not, to me, require the same soul-baring honesty that starting a novel would. (The memoir was not even a thought in my mind.) I could found a business, and no one would have to see my insides. Because I didn’t want to see them. Couldn’t stand to see them.

And the thing was, it was okay. Recovery, I learned in therapy (which I am still in, 10+ years later), is a very, very long process. And I was recovering from a few things: shunning from my community, the shattering of an entire worldview. Divorce from a man who had sexually assaulted me at least twice a week during our marriage.

I didn’t need to write a novel. I needed to heal. Writing was essential to my survival, yes, and I did write my way out of that life — but through journaling. (Which counts.)

In the healing, I would later learn, my subconscious sifted what stories of my life were for others, and what was not. Extreme pressure creates diamonds, after all. I just didn’t realize it until after the fact.

This is why I emphasize access to security and safety as the bedrock of a creative practice. Yes, people write in unsafe, insecure positions all the time. But the kind of soul-nourishing, deep and sustained practice that folks are often after — that is something that is built on access to a kind of emotional, spiritual, mental, and often physical security. On not forcing yourself to the edge of the cliff day after day without any breaks or recognition of the need for rest.

I have never liked the metaphor that writing is like opening a vein, but I think there is a truth underneath the violence of that image: that intentionally sitting down to write, preparing to write, is a process that renders us vulnerable. When it comes to wandering in the land of Creativity — each project a new unknown, unmarked on the map, one that can only be discovered through scouting and excavation — our brains do not biologically register the appreciable difference between that emotional, spiritual uncertainty and the uncertainty of, say, standing on the edge of a cliff.

My first book, Heretic, which is a hybrid memoir, was not written what some might say “consistently.” I wrote in fits and starts for years. The first finished draft of Heretic was very much just me telling the story to myself. And because memoir requires the careful reconstruction of events, and putting them into an artificial, aesthetically propulsive narrative, I revisited far more traumatic events than I ultimately wrote about. For years, I would reread my journals and go back in time, revisiting each painful memory as if it was a fragile glass statue on a shelf. I’d examine the memories for imperfections, for holes, and, ultimately, decide which ones went together the best. Each time, it felt like a piece of the glass chipped off upon my reexamination, embedding in my skin. There was a substantial cost to revisiting the past.

For me, the cost was physically literal. The week my final revisions were due to my editor, my appendix — a vestigial organ of no use, rather like many of those memories — burst. Fully burst. Infection ravaged my body for weeks. I was on so many drugs, too many drugs. I was hospitalized for the life-threatening severity of my infection multiple times (I seemed to get better once, and was discharged, only to find myself back in the ER on New Year’s Eve). I had a surgical drain put in, even though the infection made surgery too risky. On top of that, it turned out I was allergic to multiple things in the hospital — the CT contrast, certain kinds of bandages — that made the practicalities of daily care and monitoring my progress difficult.

Once I was well enough to go home after my second hospitalization, I needed help walking. Getting to the bathroom and sitting down on the toilet. Even through a lifetime of days-long migraines, I had never, ever experienced pain like that. I slept or napped on the couch and criticized myself for being unproductive — I was relegated to watching TV, because I couldn’t read. Words hurt my brain, and I cried for days when I realized books were physically hurting me to process. Because when had language not been available to me?

Even knowing the state I was in, I berated myself for not being able to write — ignoring the fact that I couldn’t stand to look at a screen up close, so how, exactly, was I supposed to go through my editor’s latest notes? My book was due, and it didn’t matter that she and my agent had told me to focus on getting better. This was an old habit, an old way of thinking: I should have written more, regardless of my circumstances. Because if words aren’t on the page, what good is anything else?

Some part of my brain, deeply committed to Productivity At All Costs, insisted that I should disregard an entire near-death crisis because I “should be” writing.

Suffice it to say, in the months afterward, I slowly, ever so slowly, began to creep towards those ideas about writing that had so pummeled my self-esteem during my convalescence. Where, even, did the belief that I always “should be” writing come from? It was an amorphous kind of guilt not tied to any specific event, but rather to my perceived lack of productivity.

My body was trying to heal, and here I was worried about my book edits. My priorities, honestly, were severely out of order. But that’s capitalism baby.

It didn’t even take a hard examination of that belief that I should always be writing, or if I wasn’t doing something else productive (aka for money) then I should be writing, for it to crumble under the weight of common sense. A human being cannot always be making, doing, producing. Always be “on” (I mean, we can, but then we burn out, or get really sick).

Output without input is bad for our systems, and for our souls. A novel, after all, is not like an Oxo bowl or Ford truck that comes off the factory line. Insert X materials, with C number of workers vis a vis D machines and Z operating time, for a predictable Y outcome.

Creativity — our enspirited relationship with Idea and Story — cannot be industrialized — much as Hollywood and the Big Four try.

And treating our creativity like a factory machine that should be always pumping ideas off the linen without doing the supply stocking of materials… does not work. It’s a car that sputters to a halt halfway down the two-lane highway, with no gas station in sight.

With no rest, no tending, no intentional input, creativity is a well that will run dry. It’s a when, not an if.

Many writers with dry wells end up coming to me, asking why their bucket keeps coming up empty — but don’t want to hear the remedy.

Those months of hospitalization, slow recovery at home, and then surgery profoundly changed my body and what it is now able to do. I could not write, or do my routines that helped me be able to write (like taking very long walks and hour-long Pilates classes) in the same ways, or sometimes even at all. I became mentally and physically taxed much more quickly. And the push-push-push, produce-produce-produce rhythm I had been able to maintain in my early-to-mid twenties, even during those crisis years, was unavailable.

I needed rest. I needed unstructured, decidedly un-monetized play. I needed to stop turning every hobby into an income stream and just have things I did offline, on my own time, because I loved them. I needed quality time — even if it was just playing Fortnite — with my partner, my sister, my friends.

In my recovery since those health events of winter 2021/spring 2022, I’ve realized I have a choice. I can either mourn the loss of my body’s capacity prior to the infection, or I can adjust and work with my body as it is now. I can discover — rediscover, even — what my body’s happy spots and limits were, when it came to physically sitting at a desk. I can find new ways to engage my mind with play that don’t require tremendous physical exertion. (It is no surprise that my own variety-needing, martial AF 3rd house that was once fed by strenuous exercise is now fed by a daily dose of often-violent video games.)

Because this is also true: in bringing me to the brink of death, my body also processed and released some pretty profound trauma that had been holding me back creatively. Those months were a crucible that revealed the relationships that were Worthy and Lasting in my life. They revealed how very, very fragile my body is — and pushed me to really prioritize what and who I loved.

I’ve always known that Writing is my first and greatest love (it’s why I’ll never have children), but that period clarified that it’s not just having written that I love, or selling a book that I love — although those things are great. I love writing itself, for its own sake. If you told me I could never publish a book again, I would still write every day, in some capacity, whether journaling, essays, or stories. I love the process. Okay, sometimes I hate the process. But I love how writing helps me think through and understand the world around me, and also helps me understand myself. I wouldn’t begin to know how to process or think through Things if writing, or practices that were connected to writing, were not available.

My (now much shorter and slower) walks around my neighborhood.

The playlists I listen to in the shower.

The novels I read every night.

The notes I make while just thinking about the story at a coffee shop.

The administrative work I do to maintain the story in a reasonable form, e.g. re-downloading and putting everything back into Scrivener, goddess help me.

I am a writer because I am in relationship with my writing, and with the stories I’m telling, every day. Yes, I have word count goals specific to my WIP, and so even though I’ve spent multiple days and thousands of words that ended up on the cutting room floor for this specific essay, I am going to be mean to myself and not count it in my word count goal — but. I have still been writing, and I would never tell myself (now) that I wasn’t.

A book is a marathon, and you have to train for it. The more you train, the better you get! And all the writing helps. That’s the whole principle behind Julia Cameron’s Morning Pages — the idea that if you’re touching the page regularly (touching grass regularly), even for journaling, then sitting down later to Work On the Book is much easier. (Truth, though. It is.)

Your creativity is a well. Yes, drink from the well! But also: how are you filling it? What are you expecting to draw from it?

Writing is so much more than words on the page. It’s a process. A way of life, even. What fuels the writing? What makes it easier? And then, of course, where is the balance of creative input? What are you doing for yourself as an artist to invest in your art?

This is what I know:

Staring guiltily at a blank screen, because that “counts” more than going outside or taking a shower, is not nourishing for your writing.

The nagging feeling that you “should” be writing every day is also not nourishing for your writing.

The expectation of constant output with no input is, in fact, detrimental to the writing process.

A writing schedule is different from a writing practice.

And creativity is not (and does not have to be) productivity.

What would your relationship to writing look like if you put those beliefs and expectations down?

What if you re-framed your relationship to writing through the lens of a practice, rather than productivity?

What if you treated Creativity like a beloved friend?

Thank you for reading this edition of astrology for writers. If you enjoyed it, please consider becoming a paid subscriber, or sharing on social media or Substack notes!

"Almost every person who sits in my client chair is exhausted, fatigued, or burned out. And simultaneously wondering why they don’t have the energy to write 1000 words a day." OK BUT WHY ARE WE LIKE THISSSS

*LOVE* this. There is so much good fermenting in our souls when we aren’t actively writing that is still part of a long term, sustainable writing practice. Loved everything about this essay.