on book deal spells, memoir as necromancy, & talmud questions: lilly dancyger in conversation with jeanna kadlec

Lilly Dancyger is the kind of person who lived more lives before she turned 21 than most folks you meet ever will. She’s many things — born and bred New Yorker, high school dropout turned Ivy League graduate, editor, teacher, writer — but that doesn’t come close to describing the life that is so richly rendered in her debut memoir, Negative Space. Is it sufficient to use some astrological shorthand and say she’s a Gemini?

Negative Space hit the shelves on May 1st to critical praise from the likes of Carmen Maria Machado, Lidia Yuknavitch, T Kira Madden, Melissa Febos, and more. If you are interested in exploring Lilly’s work, check out the anthology she edited, Burn It Down: Women Writing About Anger.

Lilly joined me over Zoom from her home in New York City to discuss skepticism, witchery, and how a creative process develops over the course of a goddamn decade.

This interview has been edited for length

Jeanna Kadlec: What is spirituality to you right now?

Lilly Dancyger: A feeling of connectedness — some feeling or believing or wanting to believe in the existence of things that are beyond what is tangible and measurable.

I go with that kind of general definition because I don't believe in God. I don't think there's some sentient being dictating how our lives go. I don't think there's a heaven or hell. But I do think there are things we can't necessarily see or quantify, or at least haven't yet measured through science, right?

JK: To build on that, does spirituality connect to your creative process?

LD: Not most of the time. I used to very actively have an altar and mark the equinoxes and all of that. At this point, it’s shrunk down to be something that's more like an internal peripheral awareness rather than a lot of active doing. Like, I try to make eye contact with the moon when it's full.

JK: Which is a ritual!

LD: Right. When I was younger, I would do a whole full moon ritual with candles and make a circle, and now I just kind of look at [the moon] and go “hey, I see you!”

JK: It waxes and wanes, as it were.

LD: Yes, exactly. I do sometimes pull a tarot card if I'm stuck, either with an individual piece of writing or thinking about the direction of my career in a larger sense. But I hardly even feel that tarot is spiritual for me — it’s a way to have ideas externally reflected back to me so that I can have a conversation with myself.

JK: That’s a helpful framework to build out a conversation around the book. In Negative Space — and I love this part so much — you call art “a spell to raise the dead.” A lot of the book considers the call and response nature between your father's art and your own writing, which had me thinking about memoir as a form of necromancy. If you could say more about that relationship between your and your father’s work, and how art transcends time?

LD: I realized after the fact that what I was really trying to do was have a conversation with my father. Creating this space felt closer to really achieving something impossible than just having the ongoing conversation with him in my head that I have been having since he died. I think that's pretty common when you lose someone, you still kind of talk to them a little bit, like imagine what you would talk to them about.

But creating this space that exists outside of time, which a book is — it’s this capsule of story and life and thought that can travel back and forth in time because it stays what it is, and if somebody reads this book in 50 years, it’s going to be the same story and the same words that had the urgency that I had when I was writing them. So by its nature, a book allows you to step outside of the world that you live in and outside of directional time, so it felt like a place I could go to have this conversation that is not possible in the day-to-day reality of life that is traveling in time.

JK: Yes. And even though the space that's being created is sort of this sacred circle, if you will, that is outside of time, the you that is going in and out of that circle was changing over the course of this 10 year process. I’d love to hear about how your creative process changed over the course of the project.

LD: I was developing a creative process over the course of writing this book or getting. The fact that I started it when I was in college impacted the trajectory of it a lot, because I was starting it within an institution, within a framework of what it was supposed to be and when I was supposed to finish certain pieces of it. When I came back to it a few months after I finished graduate school, it was like: Now I am going to start my adult life and my creative life. I was meeting this project that I started in this very institutional setting and then was like, “Okay, me and you. Here we go into the future.”

I had to figure out how to be a writer in order to write this book, and part of the reason it took so long was because I was developing the skills necessary to write the book while I was writing the book. So I kept thinking that I was done because I had reached the limit of what I was capable of, and then I would learn more and get better and realize that I was actually nowhere near done — and do it again. That happened over and over and over again until I finally had developed the skill and the knowledge and the creative self to write the version of the book that it actually wanted to be.

JK: So, I did want to ask about your book deal spell.

LD: This is one case where creative practice and witchery did come together for me. I went out on submission five different times with this book, and it kept not landing anywhere, so I went back to square one and revised and rewrote and tried again. Eventually, I got to the point where I was like, okay, I'm actually done. I can't work on this anymore, you know? I told my husband, “This is it, this is the last time that I'm going to try to sell this book, and if it doesn't sell, I’ll put it in a drawer and do something else.” And I would come back to it in 10 years once I'd established myself in some other way.

I wasn’t giving up or being discouraged — I had just reached the end of the road. I had done everything that I could do. I didn't want to live inside of it anymore. I wanted to move on and do other things with my life. It had been a decade! And I was like, after this I will have sent it to everywhere that exists that I would want to publish it, so I'm going to be out of options, anyway.

So, knowing that I had reached the end of the road with it, it really had to work this time. And I don't pray, so I was like, maybe the moon will help me out.

JK: Yes, we love her.

LD: I think most spells are just setting intention and saying out loud what you want and need so that the path opens up for those things to happen. I gathered a stack of books that I wanted my book to be in the company of, and I gathered some things that I have — you know, a rock that a writing mentor gave me and some braided clovers that a writing peer gave me and just some collected materials of support from other people in the writing world. I also gathered all of the notes and previous drafts that I still had, which was a stack like two feet high, just to say, “This is all the work that I have done to get to this point. I have put in the work. I'm not asking for something to come to me magically out of nowhere.”

I lit a candle, and I waited until the moon was as close to full as I thought the project was. I wrote down and said out loud, I have done all of the work, and now it's time for this book to come into the world, and I deserve and need somebody in this industry to recognize that this book is done and it's good and it should exist and it should be in the company of these books that I have sitting here. Then I waited until the full moon, and I buried it under a [growing] plant.

And a couple weeks later, I got a book deal.

JK: We love to see it. A successful spell and path opening.

LD: I mean, we move through life wanting things all the time. We are creatures of desire. A spell like that is just a way of making very clear and tangible exactly what you want, and saying “This is the thing I want right now more than anything else, and I’m directing all and any ability I have to call something to myself — this is what I’m putting that into right now.”

JK: There’s a conversation over text we had very recently where you said you'd been thinking about your dad as a witch, and I'd love to hear more about that.

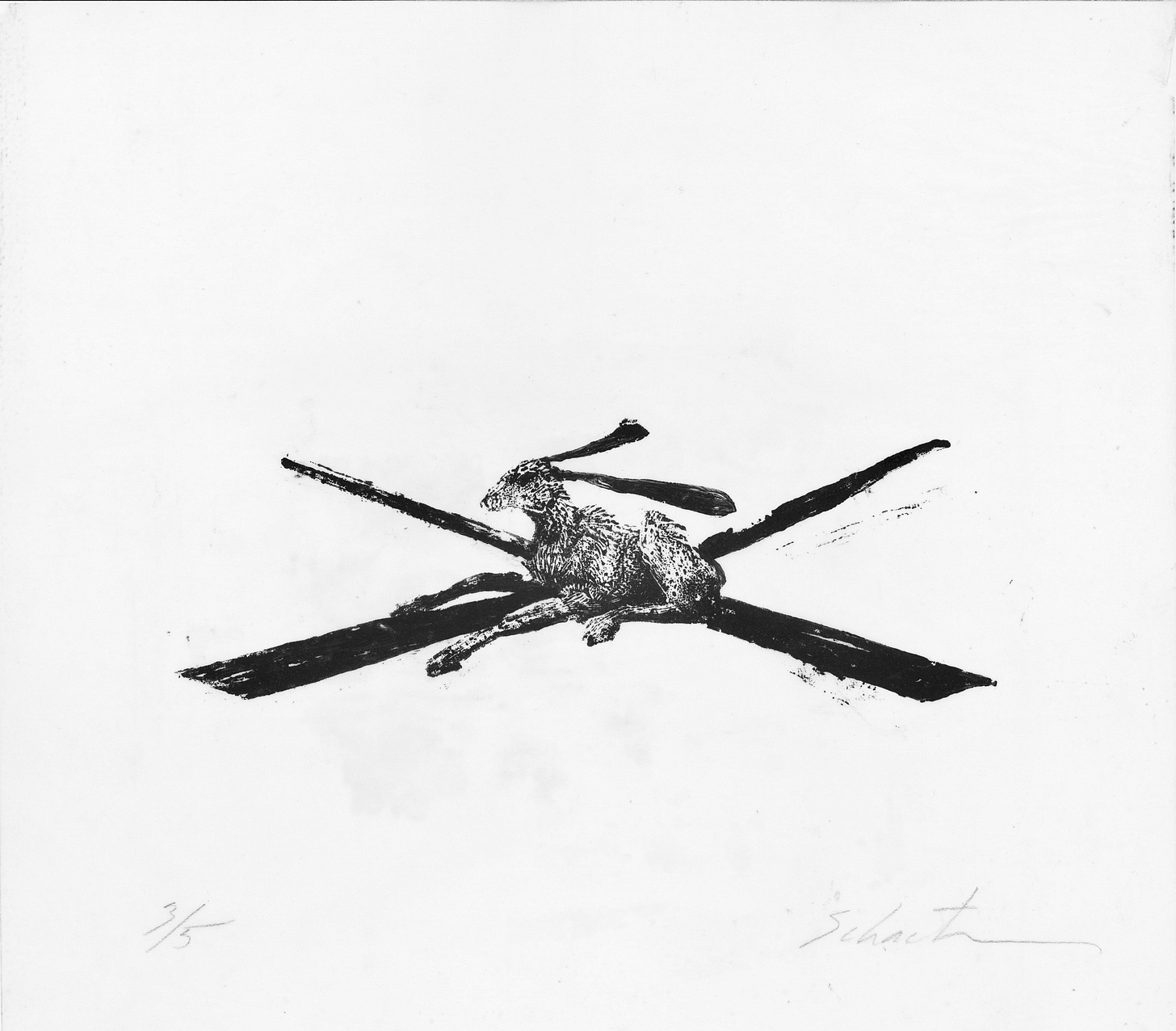

LD: I started to think of a lot of his sculptures as spells, like making work for his first love, Kathy. They split up, and he was making all this work that spoke to her and spoke about her and about the relationship, and looking at that work in the context of the story, it felt very clear that he was trying to pull her to him with this work. Then he did something similar with my mother, creating all of these talismans of her and of his love for her, creating these representations of himself and her. [My mother] told me later that he used to slip rabbit drawings into her pockets, and then she’d find them.

I know for sure that he would not put it that way, and would probably scoff at it. But looking at it through my lens and being aware of what I was trying to do with this storytelling — it felt like he was doing a lot of that, too. He was trying to draw the people he loved to him, and hold them, and keep them with this work, and also excavating and purging a lot of his own demons, externalizing stuff. Which is in a way, I guess, what all artists do, so maybe all artists are witches. *laughs*

JK: But it's so interesting — outside of whether folks literally buy into witchcraft as a “real” thing or not, there’s still the energetic idea you articulated in the beginning around these very Jungian ideas of synchronicity and connection that we can’t explain, and that kind of thing shows up in the book. There’s this inheritance you have around these powerful symbols of your father’s work that continue to come to you throughout your life — there are these incredible scenes of seeing deer and seeing stags at really pivotal life moments, which feels very spiritual, like something out of a fairy tale of the girl's lost father coming to her in a vision.

LD: Exactly. I think it's a lot of those experiences that have prevented me from being fully a skeptic, even though most of my outlook on life is pretty cut and dry and skeptical. Sometimes it's very clear to me that the deer I just saw was my father visiting me. So how can I fully be a skeptic if that is so obvious to me?

JK: Right! So, in my reread, I’m approaching the end where you and your dad start going to synagogue together. You recount having all these philosophical conversations with your father, like “Well, do you believe in God?” Obviously as someone who grew up in the exact opposite manner, these are striking scenes to read. I’d love to hear more about how those conversations have stayed with you.

LD: It was a strange experience to have one of my parents kind of find religion for the first time when I was eight years old. I had been raised in a very religion-free household up until that point. You know, my mother read tarot cards and told me about the fairies that she saw in the woods when she was a kid, and there was a little bit of that spirituality, but it was very anti-religion for a while. So then all of a sudden to start going to temple every Friday was an abrupt shift, but I loved it because we would get dressed up and go to a beautiful building and sing songs and I got to drink the little grape juice and it felt very special and fancy. I was really into it as a kid, especially because that was the start of my weekend with my father.

But I was trying to reconcile it with like, “Okay, up until this point, you told me that God doesn't exist? That it's just a lie that people [in power] tell poor people to keep them in line. So, do we believe in God now?” I do think, looking back on it, that he might have been questioning that, but it’s more likely that it was about community and feeling like he had a place. This was after losing his family, and he was living in an SRO, and he didn't have a lot of support.

I learned later in life that one of the things I really like about being a Jew is that you don't have to actually believe in God to be a Jew. Atheist Jews are very common, and nobody will tell you that you're not doing it right. Questioning and being skeptical and asking questions is part of it. That’s central to that identity, which is what my father told me — “The rules say that we have to always be learning and always be asking questions.” I was like, “Well, I'm eight, so I'm doing that anyway.”

JK: But also, it does happen to be one of the very few organized religions where that is actively encouraged.

LD: Yeah, you’re not supposed to just take things, internalize what people tell you, and believe them. You're supposed to push back and ask questions. Our foundational religious texts are all rabbis arguing with each other and asking questions and saying, “What if this?” and “What if that?”

JK: Incidentally, that's also your book — it's just constant narrative questioning. It's like, but what if this and my dad? But what if this happened? But my mom said this! It’s a constant journalistic inquiry.

LD: Which I realized after the fact. That’s one of the reasons I actually think it's a very Jewish book.

JK: Yes! I mean, it’s a journalistic inquiry, and it's very reported, but it's also a deep inquiry of the self.

LD: And, what is the truth? and what are our connections to and obligations to each other? and what is reality? and how are we tied to each other? and how do we form our identities? These are all Talmud questions.

JK: Nothing light at all. Just a casual summer read.

LD: A beach read.

JK: Have there been any particularly magical creative moments over the last year as the book readies its process to come out into the world?

LD: I think the most magical-feeling moments for me were the moments where it really felt like that conversation was happening, and where I would discover something after the fact in my father's work or his letters or whatever, that, like, really directly reflected or spoke to what I was doing — it felt like I had found my way there. It felt like it was actually a back and forth and not just me speaking into a void.

One moment which I write about in the book was with his Hunter/Hunted series of deer, which is all about the pursuit and pursuer being one, and how you could be both of those things at once. Writing about that imagery, while I was also grappling with the fact that this book that I set out to write about my father was becoming also about me — it felt like okay, yes, that. It felt like my work was reflecting his, and like his work was reflecting back and showing me what my work was in a way that felt very special and fulfilling.

Another moment was a letter that he wrote to his sister, which is in the book, about starting to go to synagogue. He was writing about how being a Jew is very much like being an artist, in that both require our continued effort. He wrote, “Both offer no answers, but a sharpening and deepening of the questions.” I said, “Yes, that's what I am doing, too!”

I’ve held onto and come back to that phrase a lot, and it’s become a kind of guidepost for me as I continue in this book but also in my work in general, as I continue to write into questions that don’t have answers and start to feel myself flailing, feeling like I’ve set myself on a task that’s impossible to complete, and realizing — it’s okay, I just need to sharpen and deepen the questions.

You can buy Negative Space wherever you most like to buy your books. And be sure to follow Lilly on Twitter and Instagram.