on making (and loving) art in hard times: r.o. kwon in conversation with jeanna kadlec

and also on creative fear, religion, and how marginalized authors get read

We are grieving. When the brilliant, compassionate, generous author R.O. Kwon and I first got on Zoom to talk about spirituality, creativity, and writing last Thursday, before our interview officially began, our grief over a week of multiple mass shootings in Buffalo, New York; in Texas; in California poured out of us. Had to be discussed, had to be held, had to be marked, before we could proceed with a conversation.

And here we are again, barely a week later. Same country, same story — and the same question: How do we keep writing in the face of relentless violence, of a state that ignores the slaughter of innocents? What is the value of inspiration, of art, in times like these?

There are no concrete answers here. We are, all of us, grieving. But we are, also, hopefully, still writing.

This interview has been edited for length

Jeanna Kadlec: I'm so happy to have you here. For anyone who may be coming to your work for the first time, could you introduce yourself?

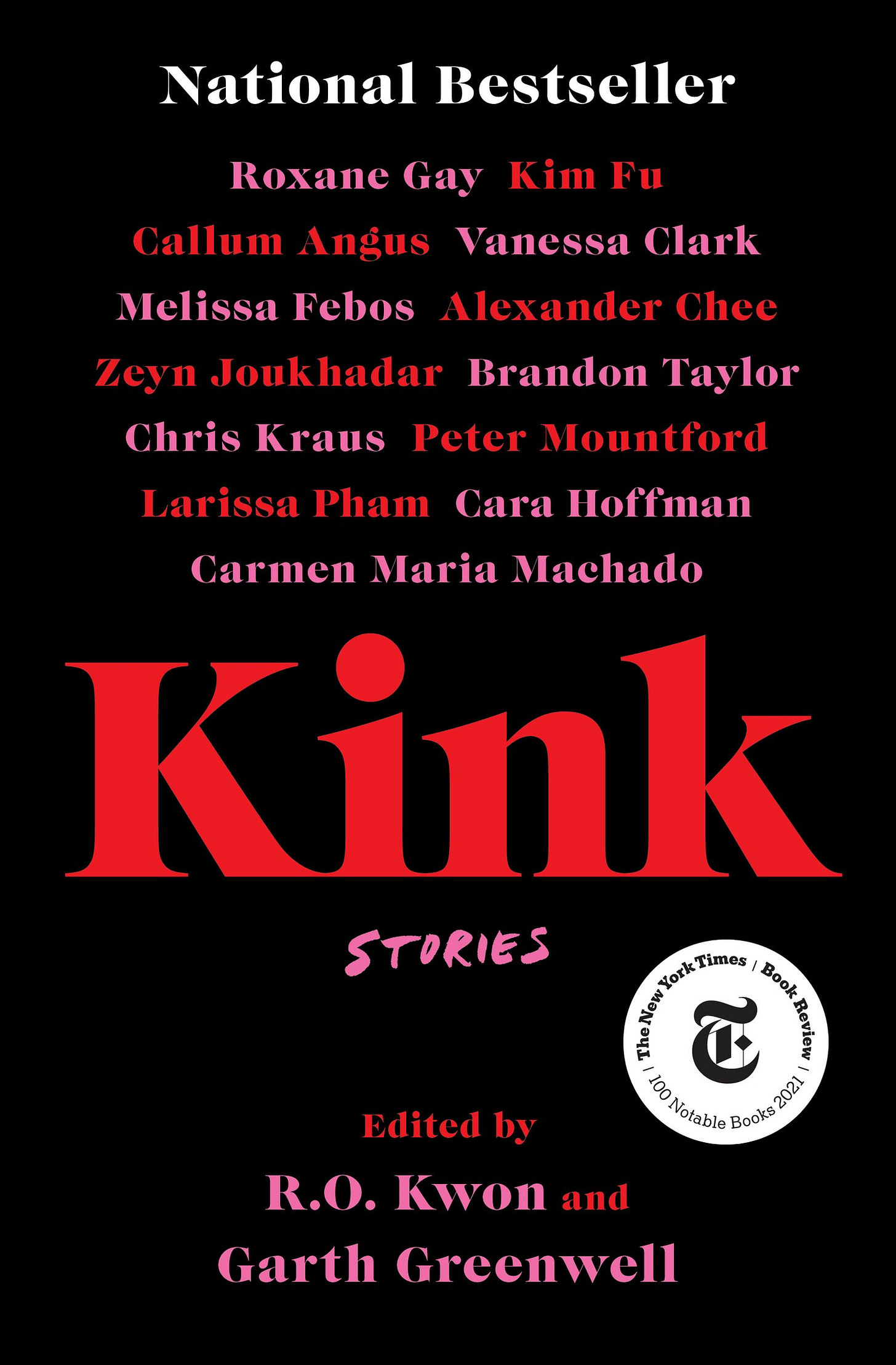

R.O. Kwon: I'm the author of the novel The Incendiaries, as well as a co-editor with Garth Greenwell of the anthology Kink.

JK: Short and sweet, and also two books that should be on everyone’s bookshelves. To kick us off and to really get us into the topic of the evening's conversation, what is spirituality to you in this moment?

RK: To be honest, I shy away from the word “spirituality” for my own life. I think this is an aftereffect of apostasy.

That said, to bring it back to the writing, there's something so mysterious to me about when the writing is going really well. I've learned that not every writer gets here, or this isn't how they work. But for me, when the writing is going really well — I'm in a sentence, super focused, all my attention is in one place — whenever I'm in that mode, I forget I have a body. I forget about the passage of time. I forget to drink water. I forgot to eat. I forget I have an “I” — like, I lose my “I.” And that's just one of the greatest joys I know, you know?

I find it so mysterious and fascinating, and I know a lot of religions have thoughts about this, that one of my best places is where I'm gone. Where it’s not about me anymore. Where all my worries, all the worries that have to do with my ego are gone. I [feel] really lucky to be able to get there. Like, definitely not on a daily basis, not even on a weekly basis, but the fact that I can get there sometimes feels like a tremendous blessing.

JK: I love that, like in the way that you put that in terms of the disembodiment — but it’s not the disembodiment that comes from a place of dissociation and the, I'm dissociating because I can't deal. It's the disembodiment that comes from being so profoundly in the moment and connected to something that's greater than. And you're absolutely alluding to so many religions that call that [experience] being connected to Source or connected to oneness or whatnot, but it's [also] being connected to story and this idea of where does story come from? And is it from the “I,” you know, when you're saying that when you're in that space, the “I” is gone. And so where is it? or where is that story coming from? Do you have thoughts on that, or a sense of that existential question?

RK: Where does the work come from?

JK: Yeah.

RK: I’ve been thinking about something Yiyun Li said about novels, that you go live there. I never feel like I'm just making random choices. I don't feel like God; I don’t feel like a puppeteer. I'm just asking the world of the book to show me what it wants to be. It feels to me — and I know this isn't quite true, but it feels reassuring to me to feel this way — as though what I'm working on already pre-exists me, and my job is to find my way there as well as I can and as thoroughly as I can. At the very least, I think I find that reassuring, because then that means there's an answer. *laughs* Then it means that there's an end point somewhere, somehow!

JK: I think of Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic, where she talks about writing as being this very spiritual process, and that your job as the writer is just to uncover these strange jewels that are hidden inside all of us, and we all have our own to find.

RK: I love that so much.

JK: Kind of in that vein, but there’s been so much happening in the world, so much happening to communities of which you're a part. Like we were discussing earlier, there were literally multiple mass shootings in our country just this week. In light of all of these heartbreaking things, what has your relationship to inspiration — that might not be the right word — been like lately? In terms of navigating the world being shitty and continuing to go to shit and also making art and trying to get to that [aforementioned, “I” losing] place at the same time?

RK: I think it's amazing that so many people are able to do anything at all these days.

So, at the start of the pandemic, I had a couple of months when I could barely write. I was reading a sentence a day, and I had a deadline to deal with, and I was just panicking. I couldn't do anything. Four different things helped.

One is, I formed accountability groups with friends where we just text each other and email each other what we've been working on and how that's been going. I currently have a few going. Two are every day and one is once a week. I really love accountability groups, and also they provide a sense of community in this continuing time of increased isolation.

Second thing, my friend Ingrid Rojas Contreras wrote this piece that I rave and rave about. It's about creating rituals. She talked about it to me as creating a holy ground for yourself, for your work. So I have several things that I do: I change the lighting. There's a certain shawl I wear or keep near me if I'm working. There's a mug that I drink from, and I can only have that mug. There's also certain music I listen to only when I'm working on my fiction. And so when any of these elements are in place at this point — at first it required all four — but if some of those elements are in place, then that's like I'm working on my fiction, or I'm reading something that is directly immediate to what I'm working on.

And that has helped enormously. I used to use Freedom all the time; I haven't touched it since I started doing this because I don't need Freedom anymore, because I don't want to disrupt my holy ground. I won’t answer texts when I'm in this space. I won’t look at email. If my husband wants to talk to me about anything and I'm working — unless it's something really immediate, like what should we have for dinner tonight? — like, if it's something about our weekend plans, that's a conversation for when I don't have my shawl on. That's been a huge part of what's helped me write.

I think the third thing honestly was at some point I was just like, well, if I had three years to live, and I knew I had three years to live, what would I do with that time? I would want to write and read and see the people I love and eat delicious food and get drunk. So the fact that the world is fucking terrifying — that doesn't change what I would do with my life, so I might as well keep doing what I want to do with my life.

The fourth thing that really helped was, well — on the one hand, I don't think there's anything selfish about making art. Books have quite literally saved my life. Reading has quite literally saved my life in some really low moments. And/but, as I'm sure you know, it can be really hard to work on something long term when the world is in such bad shape, in so many ways, in so many of my communities.

It helped me to just be like, okay, well you feel useless. So why don't we do more useful things for our communities on a regular basis! It’s like bribing my guilt, or bribing my anxiety to be like, you did this thing for other people, so now can we fucking have these two hours to work! So bribing really helped, too.

JK: I love that idea of bribing your guilt.

RK: Just like, listen, here's a carrot!

JK: I'm going to do these things, and then I get two hours with my shawl.

RK: Let me think about sentences, oh my god.

JK: To your point, like with the immediacy of the short term things that crop up vis a vis these long term projects that you're sinking into, how there's such a dissonance there and managing those two things mentally — the strategies that you just laid out are so genius. And I think will be so helpful to some folks.

I love that you brought up your writing rituals and how there are these really beautiful things that you do for yourself to enter into a writing space. It sounds like your process has perhaps changed a little bit over the last few years. To that end, do you find that it shifts project to project, or that it ebbs and flows based on your personal state of being?

RK: Oh, that's such a good question. I’m working on my second novel right now, and I've been working on it for six and a half years. It's taking a long time.

JK: But then it'll come out and be brilliant

RK: It’s so wild to be a writer, right? Like you work on something for years, and it’s like, I don't know if it's a trash heap.

In “Berryman” by W.S. Merwin, he quotes Berryman saying something like, if you need to know if you're any good, you'll never know. Like, this isn't the life for you. You’ll never have that certainty, so just keep going.

JK: Oh God.

RK: With this book, I've been having a relatively high frequency of panic attacks and anxiety attacks. It’s almost certainly because it's centered on queer Korean women artists, and I'm Korean, and I’m queer, and there's sex, and kink is in there. And I just know that a lot of people are going to think it’s about me. So I think that terror of revealing myself is running really high, even though it’s fiction, even though it’s a novel.

I also know that a lot of people will think central male character is my husband. This has been such a problem that one draft my editor saw, she was like the husband character — he's so nice? Why is he so nice? And I was like, honestly, I think it's because I just feel so bad that everyone's going to think it's my husband. So I’ve made him a really great dude, he's going to be like the kindest fucking dude. And my editor was like, ohhhhh yeah, he's not a real person right now on the page. He’s just benign. And I was like, you're right, I’ve got to make him less angelic.

But I also do know that fear is one of the most reliable signposts to what I want to do next with my work. Cause the fear is saying there’s something really hot over there, so I find it very useful for the work to walk toward that fear — even if it's rough on one's body and anxiety levels.

JK: There’s something really urgent to noticing the fear and walking toward it, and something really brave, too, even when it feels awful. It takes a lot of vulnerability and self trust. Maybe bravery is the wrong word. But self trust — it takes a lot of trust in your instincts to do that. That is very notable and maybe a sign of being more seasoned in the work, too.

RK: I like that as a framing of, maybe one is able to go closer toward that fear because it’s your second or third time around. I don’t know if you’ve read Solmaz Sharif’s Customs yet? The last line of the book in her Acknowledgments is, Thank you, fear, that's enough now. It’s so beautiful.

JK: Oh, I love that.

RK: The fear is trying to protect us. Sometimes it's a guardian angel, but sometimes it gets really noisy and it's like, okay, thank you! You can back off a little bit right now.

JK: Especially when you're describing your body as having really disruptive physiological reactions, because historically we're just hardwired for fear to mean survival. And you're like, no, I'm literally in my house! I'm fed, I'm housed, I'm fine. I'm just scared of creative stuff! My life is not in danger. We don't have to shut down.

RK: Nobody is physically chasing me right now. And then your body's like, they definitely are.

JK: Twitter is chasing me in my brain. *both laughing*

RK: Yeah, the brain needs to catch up with our current reality. Slightly less chasing for now, for now, knock on wood.

JK: Thank God for anxiety drugs. I have to say, I personally don’t know where I’d be without them. Very grateful.

I super appreciate your vulnerability and transparency in sharing that. Not to do the stereotypical white men don't have to deal with that because I assume that when they're being vulnerable in their creative work, they probably also do. But what you were describing in terms of, this isn't autofiction, but people will think it's autofiction, there are certain categories of writer who simply do not have to deal with that immediate interpretation and critique of the work in a way that women of color do and that queer people do. And so your anticipation of that is so real.

RK: Anyone who is marginalized has to deal with this. The demographics match, therefore, this must be entirely autobiographical. All women, all people of marginalized genders. All queer people for sure.

And I so believe the reverse — you know how there’s this idea a lot of people have, that men are more able to write women, or that white people are more able to write people of color, and I honestly believe it’s the reverse if anything, because marginalized people have had to learn so much about how a dominant group behaves just to get by. Like women — not all women, of course — but I feel like I have a PhD in men and in white people.

JK: Who knows better than anyone who's trying to survive within a culture trying to kill them, about how that culture works?

RK: Queer people know so much about straightness, you know?

JK: Absolutely. To change tacks a bit, I did want to ask about your religious background. If you could speak a little bit on how religion, and your upbringing within religion, has informed your relationship to creativity and reading and text?

RK: That's such a great question. So my family was really Catholic, and then I turned really Protestant. I was mixed up in both starting in junior high, largely because my Protestant friends’ churches were so much more fun. All the ecstatic, charismatic, people dancing and yelling is way more fun for a kid then the long ass Catholic services. I loved the immediacy of access to what I then believed was God.

But something about that foundational grounding in the Catholic Church — one thing it did leave me with is a great faith in the power of ritual, in just acting as if. I really do believe that if I just sit down every day — I know that doesn't work for everybody, nor is it even available for everybody. But for me, I don't have kids. I tend to try to work every day, and I find that the work is more responsive to me when I work every day. Even when I sit down and feel totally bleak. Go sit down, go to the page. Just do the act. It's never failed. Even if you sit there and you just flail around and you delete everything and you feel tremendous despair and wonder if you should have done something else with your life. Even if it's one of those writing days, you know? That’s still something. That still leads somewhere, I think. None of it really feels wasted.

I appreciate that faith in the power of ritual. I feel as though it's been very strengthening.

JK: There’s a very powerful component — as damaging as so much of the church can be, that sense of faith in the unknown is still so available, it sounds like, for your work.

RK: I don't know if this is related to faith at all, but I feel as though there's something where I feel as though none of it's wasted. Especially as somebody [for whom] it takes me forever to write anything. And I throw so much away. I delete so much.

This is just a low key example with The Incendiaries. I spent, I don't know, three months? six months? on 100 pages told from Phoebe’s, one of the character's, father's points of view in 1970s Korea. I researched so much for it. I wrote the whole thing out. And I just threw it away because it wasn’t working. But I believe that getting to know him that much better really helped inform the novel, and that it's in there, even if he takes up maybe two pages of space total. There’s faith that if you’re working at it, it’ll probably go somewhere. And if not, that’s okay, too!

I think it's just so lucky to get to love anything this much. To get to be this fucking obsessed with something. Not everyone has this. Even though it’s the torment of our lives. *both laughing* I don’t know of any writer who would call themselves happy except one. And I was like, wow, you’re wild. Tell me all your secrets.

JK: What even is happy?

RK: I don’t even see it as an objective at all.

JK: I feel like I have a lot of joy in the work. I unpack this in my book a little bit, but I feel like I have a lot of what the Christian sense of joy is? And I'm continually trying to untangle that for myself. And I'm like, No, it's like queer joy. But I still have a lot of that deep seated, very baseline settled joy that's not necessarily like, happy, but it feels like very content and foundational — but it's like the base of a very anxious life, still.

RK: I love that. There’s this deep layer of some kind of joy, and then right above it is AHHHHH! *both laughing*

I wonder if part of that joy is just the incredible luck of feeling as though you might be leading the version of the life that you are best suited for. I don’t believe anyone put me on the earth, but if I did, as a figure of speech, I realize I was put on the earth to fucking play around with commas until the end of time, and that's so lucky. And even if I think, is there any other kind of life I would want? then I'm like, well, it'd be really cool to be a poet or maybe a composer, but it’s all along the same [trajectory]. I don’t want to be a tech mogul. That sounds like hell on earth anyway!

JK: You’re bringing all this beauty and joy into other people's lives through the work and getting to sit in that joyful and light space where you get to ultimately randomly, unpredictably bliss out. To go back to the beginning of what you were saying, sometimes you get access into this — whatever space that is.

RK: Because I know you've talked and written about how you had a different life before this. I imagine that getting out of that and getting into this life that is for you — that must have been so very foundationally freeing.

JK: Very freeing. It’s also so interesting to me that there were so many years where I just stopped writing, as I was going into like that cocoon, if you will. And then when I was coming out of it was when writing opened back up for me. It was like I wrote my way out of it. And none of it was good, you know? But the process was so important, and that process of writing can be just so vital for connecting us to ourselves.

RK: That’s so beautiful. I’m so sorry that you had to do that, but writing was your rope out.

JK: I’m right there with you on, thank God we get to do this! Not God, but, whoever.

RK: Whoever!

JK: Last question! Have you had any particularly memorable or creative moments this year, or any moments of inspiration or being at your desk or talking with other writers where you just had an oh my god! This is why I do what I do moments.

RK: I think I wanted to write the book I'm writing right now in part because I've never read this particular book, with these characters leading these lives. I've spent so much of my life feeling so lonely, and it brings me so much joy to think about being able to write this book and being able to help someone else feel less lonely, you know? And maybe it's not to somebody else, but it's like my seventeen year old version of myself who felt totally alone in the world and just trying to help her be like, you're not alone. You’re not wild. You're not destined to be alone because you're so weird, because you want things that nobody else seems to want in your extremely Christian small town in California.

Those are often some of the most meaningful responses to what I write, is when somebody writes and says something like, thank you for writing something that helps me feel less totally alone in the world. That means the world.

JK: That's really beautiful. Those are the books that save people, that help us feel connected to ourselves. What a gift to inner child, baby Reese —

RK: You feel really weird right now, but you’re seventeen, you’re in high school. There is a world out there.

JK: You’re going to have the life you wanted, or that you didn't know that you wanted.

RK: That’s part of what's so incredibly evil about these fucking book bans. I’m thinking about the number of queer people I know who read a queer book for the first time from their school library and were like, Oh, my God, I'm not alone. It’s some small town without a bookstore where the library is what kids have. And yes, people can read things online, but the internet didn’t help me when I was a kid the way books did. They might be a kid with parents who can’t come to terms with them being queer. They’re not going to be able to order that fucking book online. They probably don't have credit cards. Where are they going to get this?

P.S. Be sure to follow R.O. Kwon on Twitter! You can pick up The Incendiaries and Kink wherever you most like to buy your books.

P.P.S. In keeping with the theme of this newsletter: Donate to your local abortion fund.