on writing as a spiritual practice: melissa febos in conversation with jeanna kadlec

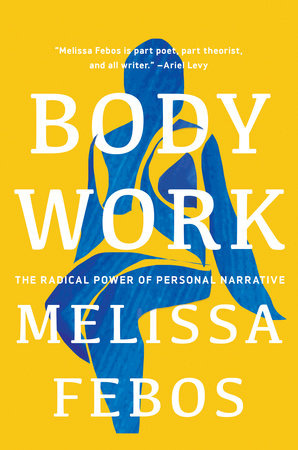

After three critically acclaimed memoirs and years of teaching, Melissa Febos is bringing everything she’s learned about writing to the page, sharing her life’s work with us in Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative, her first craft book which is available on March 15th. (Pre-orders are love!)

Reading Melissa Febos’ work changed my idea of what personal narrative could be, and I know I’m not the only one. The good news is that Melissa is an incredibly generous teacher, literary citizen, and friend who readily shares her own experience, the embodiment of the idea “a rising tide lifts all boats.”

Melissa is the author of memoirs Whip Smart, Abandon Me, and Girlhood, a national bestseller. She is also an associate professor at the University of Iowa, where she teaches in the Nonfiction Writing Program. She joined me over Zoom from her home in Iowa City to talk about the spirituality of the creative process, pedagogy, being in a “not writing” phase, and more.

This interview has been edited for length

Jeanna Kadlec: I know and adore you and also your work. But for folks reading this who may inexplicably not be familiar with your work, if you could introduce yourself to the Astrology For Writers audience?

Melissa Febos: My name is Melissa Febos, and I am a memoirist and essayist. What else?! I've written probably a thousand pages about it, because summaries defy my cognitive skills, so instead I have to write books about who I am so that I figure it out, which is probably as good a description as any.

JK: Honestly. What even is saying you're a memoirist and essayist if it's not just, I write about myself.

MF: Writing is my primary mode of thinking. I write a lot about addiction, recovery, sex work, feminism, queer things. My wheelhouse — not by choice, but sort as defined by my instincts — tends to be things that I and a lot of people are afraid to talk about.

JK: Which is pretty rad and draws a lot of people to your books. Certainly, I think, it’s what drew me to them.

To dive in, what is spirituality to you in this moment in time?

MF: I think that increasingly, the older I get, the more integrated the primary elements of my life [become]. The pieces are increasingly integrated, increasingly intertwined.

Right now, it's pretty impossible for me to separate my spiritual life, or my conception of spirituality, from my creative life, from my social life, from relationships. It exists in my relationships, in my creative practice. I mean, I have a meditation practice, and I do a specific kind of journaling in the morning. I have a conception of a kind of higher power. But it's all completely embedded in every part of my life.

So that's less of an answer to what it is, but more sort of how it is, which I guess is easier to talk about, right?

JK: I think when that integration of things becomes so mundane, there’s a lot of beauty, and [there] is just the lived everydayness of it. Like, the breaking down of the barriers of the spirituality of organized religion that tends to section things off.

MF: Among all of the big parts of my life — my creative practice, my relationship to my body, my relationship to other people, my relationship to my job — I think the principles that govern the way I think about those things can all sort of be described as spiritual. I am generally oriented around ideals like love and service and honesty and presence. And I want to say resistance, but I think that fits into the honesty part, right?

JK: Can I ask how that started to coalesce for you? Toward the end of Body Work, you write, “As a child, I did not understand spiritual, cathartic and aesthetic processes as discrete, and I still don't. It is through writing that I have come to know that for me, they are inextricable.”

I'm curious if you could say more about that, about what that process of coming to understand their inextricability was like for you?

MF: I think at first it was intuitive. And this is true: A lot of the most fundamental and profound understandings that we arrive at as adults, we understood intuitively as children.

Like when I was a kid, I felt a very clear connection with what I refer to as god. But it's a very capacious conception of god in terms of nature, the universe — like an organizing intelligence of which I am like a microscopic part. And I felt a connection to that in very ordinary experiences of nature, through art, in connection with other people, in connection with my own body, just like everywhere. You know what I mean? There was no hierarchy to the entry points to that connection or feeling. For me, creative practices, absorbing art, being in connection with nature, being in connection with my body, writing, like the channel of writing and the way that that expressed something that my self-conscious mind could not access — I didn't have words for it, because I didn't objectify it in any way. I just understood it, and did it.

I think as I got older and became conditioned to the hierarchies and belief systems of our society, I became estranged from that in certain ways. They were replaced with these other motives and ideals. And so the work of my adulthood has been primarily the work of expelling those belief systems that I didn't choose and returning, restoring, developing and cultivating that integrated relationship to my understanding of life and what matters to me.

JK: That’s a big mood. *both laugh* The work of adulthood being the work of expelling and just processing and and trying to purge that which is constantly trying to invade.

MF: Yeah, it just has to be a life's work, right? Because the bombardment of ideas that are not ours, like the big “ours” that are not mine, and that seek to make me complicit in my own disempowerment — it doesn't sleep. It’s always happening. This has been happening since the moment of first consciousness. And so if I don't integrate a resistance to it and a counter to it in every aspect of my life, I will just be in thrall to it, like I don't have a chance. If I don't sort of collaborate with other people in that work, I have no chance of resisting it, let alone expelling it.

JK: This fits really well, actually with a question I really wanted to ask you, given that you teach creative writing. To ask how this dimension of a spiritual component to creativity — does it inform your pedagogy? And if or how it informs your classroom, given how institutionalized writing programs are?

MF: My understanding of teaching is really one of sort of how to create a space that integrates all of these things we're talking about within an institution whose mission is actively counter to that in many ways. Like, I work for an institution of the state. And it is an enormous privilege to make use of its resources for my own personal mission, which is counter to the historical momentum of institutions like that. It was not created for people like me or most of my students to do the kind of work we're doing, right? And yet.

At this point in my life, I'm doing the same kind of work in every space that I'm in. So in my classroom, I rarely frame the work in spiritual terms, but it is always existing in spiritual terms.

For me, I am communicating a perspective of art and the life of an artist as one in which we must integrate our politics and our spirituality and our moral beliefs and the rigor of our attention. For me, the most satisfying life, the most sustainable life is that kind of life. I'm not necessarily prescribing that for my students, but I'm modeling that for my students, for sure. And I'm designing a space in which that is the foundation, where we are trying to cultivate an awareness that allows us to expel the ideas that don't come out of our own experience and are not in the interest of our survival.

JK: I love all of that. I think of some of the really harmful ideas and lessons that can get imbibed in a creative writing educational environment about who counts and who gets to write and who doesn't get to write. Everything you're describing just sounds like really potent medicine.

MF: Yeah. I see writing as, for me, a ceaseless process of awakening, of always moving towards more awakening, which is a practice of humility. Just like, an unending practice of humility and expanding my notion of where my beliefs come from, what I'm perpetuating, and what is possible. I'm trying to encourage my students to always do that. It’s also the work I'm doing in therapy. Would I ever frame it that way for my students? Never. *both laugh* I don't want to terrorize them! You know what I mean? There are limits! But I am constantly, lovingly pushing them towards questioning their beliefs and the things they take for granted and where those things come from and who they serve.

I read a lot of mysteries, right? It’s always the question that person trying to solve the mystery [is asking]: Who does this event benefit? When [do] my biases pop up, or my students’ biases, or the things that we take for granted? Even the choices in our work — like, where do we break a paragraph? Why this diction instead of that diction? Why is this seen as serious work while this isn't? What does intellectual mean? Wait a minute, where did that come from? Do I take that for granted because it was embedded in me before I even knew what my ideas were, or have I come to that as a result of my own observations and experience and listening to other people?

JK: That sounds like really incredibly valuable work for your students to be doing, but also for a writer to continually be called upon, to not take our own crap. To not take our work for granted and not be on autopilot.

MF: To think about it sometimes is super exhausting and overwhelming where it's like, Oh, I want to constantly be conscious of everything. We can get frozen with that kind of self-consciousness, but I don't think of it as like a ceaseless scrutiny of everything. It's really just like cultivating a different set of instincts that will eventually operate on their own. And I've experienced that in multiple ways in terms of my work and my thinking and my relating to other people and to my own body and and whatever as a reader, just like becoming a more critical thinker, basically.

Like, I taught a class last night and at the end of the class, as my students were walking out, I had the urge to be like, I love you! The same way that I feel after a long phone call with a friend or I go to one of my recovery meetings or I have a therapy session. I want my heart to be more open at the end of it. I want us all to have stepped into more vulnerability, more trust, more wakefulness, more presence. And most of the time, that happens.

JK: There’s so much intimacy, though, in sharing work and in being in community and in groups where that kind of work is shared, whether that is a class or a writing group or what have you. The kind of work with memoir and personal narrative does build a trust and an intimacy among people in really powerful ways.

MF: Absolutely. It’s funny because sometimes you hear creative writing teachers lament kind the lethargy that can come from teaching people something that you know they're not going to quote unquote succeed at — like [this idea that] most creative writing students are not ever going to publish anything.

But I never doubt the value of what we're doing in the classroom because we are using writing as a tool to learn how to be in the world, how to be in relationship with each other, how to be in relationship with ourselves, how to move through life in a way that is opening. Like, I don't give a fuck what they do after they leave my class. I trust that they will be better equipped to be in intimacy with their own experience and with other human beings, you know?

JK: And that's how you talk about writing in Body Work, trusting that you're in relationship with your work and with yourself in a way that is increasingly less afraid. Perhaps that is never completely unafraid, but that is increasingly less afraid to be that way with yourself and with your own experience.

MF: Yeah. I start all of my classes, the beginning of the semester on the first day, [with] a preface to the semester [that] gets longer and longer every year, because there are so many ways I want to frame the course for them that represent a radical shift from the way they understand classrooms or school or writing.

It’s basically the conversation I have with myself implicitly every time I sit down to write where I'm like, okay, look: We are going to have feelings in this class. It's going to be uncomfortable sometimes. Feelings are not an emergency. This is not group therapy, but many of us will have a cathartic experience in this classroom. I have everyone agree to a basic confidentiality, where we're not going to be talking about each other's work with people outside of class. I tell them, you can bring your feelings. We are not going to treat it as an emergency. If you start crying in class, I'm just going to ask you if you want to stop reading whatever you're reading, and we're going to move on, and you're allowed to have your feelings. I encourage everyone to attune themselves to their own psychic and emotional safety. If anything feels like too much to just stop. There's no forcing it. We want to take risks, but we don't want to endanger ourselves.

It’s just this whole sort of defining the space as one that is challenging and also safe — not in the way that they have come to understand safe spaces necessarily. But [one] where we're all negotiating our own boundaries and have the freedom to do that right. And all of that I've learned from my own writing practice.

JK: That sounds like a class that I would have wanted to take.

MF: It's the class that I wanted to take! Just like we’re writing the book that we needed to read, I'm teaching the class that would have been perfect for me when I was that age, you know?

JK: And how fucking cool that you have gotten to create that.

MF: How fucking cool that I figured it out. I could complain like any academic til I'm blue in the face about the institutional structures and the negative parts of working within an institution. But my god, I never lose sight of how fucking fortunate it is that I have a job where I get to be my whole self and also wear whatever the fuck I want and also curse the way that I do. It's amazing.

I've been working full time since I was a teenager. And a job was something in which I inevitably had to compromise every form of integrity that I knew. I could never be myself in any kind of complete way. I was always subjugated by the worst kinds of power structures in our society. And my classroom is such a radical space. I think I recognized early that being an artist, that if I were to survive psychically in America, I needed to find a kind of loophole in terms of labor. I'm so fucking glad that I did.

JK: I do want to pick up on something that you mentioned, which is just to ask about your writing practice. You said that the [classroom] preface is similar to your own entry to how you create a space — there's a spiritual component to that ritual. I'd love to hear a little more about that.

MF: I was just talking to a friend this morning about how I'm accepting that I'm not writing at the moment. I published a book last year, I'm publishing a book this year. It’s a pandemic. The list goes on. I am just in a recuperative space where I have to put my creative energy into revising the way that I live in some really profound ways. For me right now, it has to do with health and body and labor and work and my relationship to that. So I’m just trusting that it's there, and that it will be waiting for me. You can't drive a car with an empty tank, you know what I mean? And I just need to accept that and not have scary punitive thoughts about it when it's not possible.

I will say, when I am in a writing space, it is spiritual in that I am trying to invite an intelligence that is beyond my comprehension. I understand these concepts of muses and being a channel — like that makes so much sense to me because I do think it's in me. It's an intelligence that is mine, that is shared, but it resides way below. It is not accessible to the part of my mind that is thinking and making outlines and trying to make everyone like me and trying to be a good employee. It's not the intelligence, even, that comes from the books I read or the conversations that I've had. It comes from my conception of god, which includes like my higher intelligence, that which is connected to the larger design of existence of the cosmos.

I really believe that. And so for me, my rituals are really about quieting the radio of my regular thoughts, which means getting away from email. It means getting away from the internet. It means getting outside my house. In a practical sense, what this means is on the days when I'm writing, when I'm in a writing phase, it has to be the first thing that I do, because I just know the limits of my own resistance to the chatter of my own brain, the needs of other people, the noise of the news. And like, my Outlook dinging. I have to get up and block myself from my own internet and turn my phone off or leave it in the bedroom and get a cup of coffee and go to my desk. I need a clean palette of consciousness in order to make space for that. Like the opening to the sublime in me narrows as the day goes on.

JK: Relatable.

So first off, I just want to say, I so appreciate your forthrightness about how we aren't always producing. It waxes and it wanes and it really needs time to rest and to be fallow. And I feel like we all know, but not enough people openly talk about having periods where, like, I'm not writing right now. And that's a big thing.

MF: I feel like my whole life of writing classes, I've heard people being like, Oh, there's lots of things that are not writing, and we pay lip service to that. But the only thing that counts is word count. It makes no sense. I mean, it makes perfect sense when you think about how we live, particularly in this country.

But truly, the only useful word count I can amass right now is my morning pages, and that is so important. I'm in a period of growth and a period of output. It’s been a really radical shift for me to even think of reading as part of the writing process. Like last year — it was a global pandemic, I moved across the country, started a new job, had this chronic pain condition. And I was like, I understand that writing is a place of refuge for me, and so I actually think I need it right now or I'm going to get really fucking depressed.

My days were so demanding and exhausting that I started getting up at like 5, 5:30 in the morning. Thankfully, it's the pandemic, so there was nothing to do after 8pm except go to bed. So I would go to bed early and get up [early], and I would spend the first three hours of the day as big umbrella writing where I was reading or sometimes researching, or just making lists and notes. Trying to open that channel. Trying to find connection. Trying to make space for my intelligences that have nothing to do with time management or measuring word count. It was a life raft. I think I would have lost connection with myself in a really devastating way if I hadn't done that.

JK: That makes total sense. And [thank goodness] there are periods of life, whether because of internal needs or because of the external situation — what a hopefully once in a lifetime situation these last few years have been, like, knock on wood — where the writing is available. But also, as the last few years have [shown], it can’t be the one thing for that long a period.

MF: Right. I think it goes back to [how] the most sustainable writing practice is one in which it is also a spiritual practice. The product of what I was writing in those mornings doesn't really matter. Like, I did publish a lot of it, but it was part of my survival, you know? I write about this in Body Work — because writing means so many other things to me that have nothing to do with publication and nothing to do with other people's perception of me that it ensures that I will do it until the day that I die. Like, I just will always do it because it is imperative to the way that I live.

JK: There was so much that was in Body Work that that felt like a life raft personally as I was going through my own memoir revisions. But also, it was just very relatable, and it always feels good to read something that resonates on a personal level. So much of it is about craft, but it's about writing as a way of living, that's not just wrapped up in writing for the sake of getting your work out there. It’s about what you're saying, of writing as, this is just how I'm being in relationship with myself, and this is the way that I do that.

MF: What a comfort. Imagine if the point was to get money.

JK: A terrible point.

MF: I mean, it just sounds like hell. This is partially enabled by the way I've decided to live, like I've decided to have a job and not be dependent on writing, partly because it means so many other things to me that it can't be contingent on it on that form of productivity.

But what a relief, right? that I don't have to try to exert control over how I'm perceived or what happens afterwards. That the best part of writing has happened way before my work is ever published. And you have to publish to figure that out, but it’s been confirmed over and over and over again for me.

JK: I love that.

You write about confession at length in the last chapter of the book, and how it's part of knowing and transforming the self. I did want to ask if or has the act or function of confession felt different across your different books?

MF: Yes and no. You know. I think I wouldn't have described my first book as confessional, because I was still really entrenched in a lot of the internalized biases that I write about in Body Work. But when I think about the experience of writing that book, and the fear and faith involved in externalizing those thoughts and feelings and experiences and the incredible force of it — like the terror and relief that marked that experience. It’s very, very confessional.

I was a different person in many ways when I was writing each of those books, and writing those books transformed me in very specific ways. Like Abandon Me, I wrote while I was in the experience that was happening. I had no distance from it for a lot of writing that book. I was writing my way through an experience, and so I was not able to structure a narrative to make a story out of my experience. It a different kind of meaning making that was much more reliant on lyric modes and even phonics. It was just like really through the language. It was more poetic.

But the thing that they all have in common is me putting words to things that carried shame, that I thought might be unspeakable, that I was terrified of being seen in. The act of writing them was a practice of faith that in doing so, I would be loved. And I would never have articulated that for most of what I've written, like, I'm writing this because I believe that on the other side of it I’d find love, right? But that has always been my experience. And I think as I progress as a writer now, I feel so much more secure in that faith. Like, I'm someone who has practiced her faith.

If writing is a spiritual practice, my faith grows because every sort of leap that I take, I've just been caught over and over and over again by my practice — I'm gonna cry talking about it — by myself, by my community, by total strangers that read the book and write to me and tell me that they felt caught in reading it. So that practice that I describe, like I so identify with that like Jewish process of repentance and confession because it is so forgiving, right? It's so loving.

It's like just the act of saying it is worthy of love, the idea that the love is always there but we can't feel it until we take that leap of faith and allow ourselves to be seen by god and that it's just gestural, right? I think it's exquisite. It's so beautiful, and it is like all of those practices that we're talking about — it all boils down to that for me. I just have to believe that that is at the core of it and that that's always possible. Whatever the constraints of my given situation, there is a way that I can practice that even if it's just within myself. That is what saves me from nihilism and pessimism and cynicism and suicide, honestly.

JK: That is, I think, so true, and that was so moving to hear. I mean, love is at the center, and I think the experience you're describing is also what so pulls readers to memoir continually is the experience of the author that they're living through vicariously, but also hopefully being inspired, being drawn to — that's the spiritual transformation in the genre, just that aspect of the human condition that they're just being drawn to over and over again.

MF: I think it's instinctive. It goes back to that child intuition and connection with the divine in ourselves and in everything. I really do think — it sounds like hyperbole — but I really do think that memoir is the song of that, and we're so hungry for it, we're so desperate for it, because we've been so estranged from it. It really does feel like creating a kind of spiritual community that exists ambiently, right? Like, I don't know everyone who connects through my work, but I know the lineage from which it comes, like all of the books that I had that spiritual experience reading and that I felt loved by and that modeled that for me, and I have some awareness of the people that have that relationship to my work, and like — who really cares about anything else? When I'm in touch with it, I don't give a shit about anything else.

JK: Word. Those are the kinds of books that save people, and that I know have saved me, and also that you're saying that have saved you.

MF: Yeah. It's so real.

You can pre-order Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative wherever you most like to buy your books. Be sure to follow Melissa on Twitter!

If you would like to financially support this newsletter to help continue the work we’re doing, be sure to subscribe:

this is beyond delightful

What an exquisite interview. I discovered Melissa Febos a few months ago and have never resonated so deeply with a contemporary writer. I’m also an astrologer/writer so I am ecstatic to have discovered your Substack and your work! Thank you for sharing yourself. 🙏💜