queerly devoted: charlie claire burgess in conversation with jeanna kadlec

on reclaiming the self and spirit and also deity

Before diving into this gorgeous interview — the first author interview in almost a year! — I want to quickly remind folks that the early bird pre-sale for

’s and my new lecture Creativity Through the Houses ends tonight!Honestly, all you need to know is that I cried both during this interview with the brilliant and generous and then again while editing.

Charlie’s spiritual wisdom and intellectual rigor is a gift to us all (subscribe to their newsletter!), and what they have to say about both the history they have recorded and the difficulty of the present moment will, I think, resonate for many of you.

How lucky we are to have Charlie’s mind and spirit at work in the world. They are a scribe, a poet, an illustrator, a historian, a Renaissance artist for our times, whose work perpetually calls us back to ourselves.

Charlie’s latest book, which I had the great good fortune to blurb, is the smart, thought-provoking, deeply moving Queer Devotion: Spirituality Beyond the Binary in Myth, Story, and Practice, available everywhere books are sold on May 20th of this year. Pre-ordering it from your local bookstore is extra love!

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Jeanna Kadlec: Well, I adore your work, and I imagine a lot of people are familiar with your work, perhaps through the tarot that you've done — the Radical Tarot and the Gay Marseilles deck, which my wife loves. It’s actually on the desk right now. Your work has a very prominent place in our household.

But in the case that folks who are reading astrology for writers may not be familiar with you and your work, I'd love it if you could introduce yourself.

Charlie Claire Burgess: I'm Charlie Claire Burgess — just Charlie is fine. My pronouns are they/them. I am a queer and trans non-binary artist [and] author. My books are, like you said, Radical Tarot, and my next book is Queer Devotion. Two decks: Fifth Spirit Tarot and the Gay Marseilles Tarot. I'm a technically a fiction writer, and I’m working on a novel in the background, which I shouldn't even be talking about, probably.

JK: As someone also working on a novel in the background, I'm very excited. We need all the queer stuff from gorgeous queer creators. And I will be linking to your newsletter here, but you also recently wrote this absolutely gorgeous piece about transitioning in the end times. I think everyone should read it. It's so vulnerable and so beautiful.

By way of kicking us off, because we're going to talk about the writing. We're going to talk about Queer Devotion, a book that I was very lucky to get to blurb. I want to pull back for a minute and ask what spirituality is to you in this moment.

CCB: Totally. In this moment in time, spirituality for me is a form of resilience and resistance. It feels like a root system that's kind of keeping me grounded and present and nourished during these times when everything is so hard and scary, and democracy is falling apart and fascism is rising. And people like me and my partner and you and your wife are being targeted for who we are.

So right now, having a spiritual connection, especially to spirits and deities and just the universe, that is bigger than what's happening, but also deeply enmeshed in what's happening, is keeping me hopeful and sane. Not in like a, everything's going to work out, love and light, Jesus take the wheel kind of way.

*both laughing*

JK: The way that we both grew up with.

CCB: Exactly. Not in an, I'm going to sit back and hope and God will make everything okay sort of way, but instead in way that connects me to this lineage of queer spirituality, queer divinity that goes back through the ages, and how it's been impossible to fully stamp that out. How people have tried: regimes have tried, religions have tried, and they have not been able to succeed. And so we're just going to keep fighting, keep being here, keep singing our joy at the top of our lungs.

We’ll still be here. We always have been. We always will.

JK: That's so beautifully said. And the way you describe spirituality as a root system, I can feel that, like staying with me already. The image of roots is something that's very important in my own collection of metaphors and images that each writer-artist has that they perpetually draw from. So that's really resonant, and I think really speaks to what you're saying, that your work especially, I mean, in this book, but also more broadly, is very much about looking to the past in order to look forward.

You don't just go back to the past in this book to [explain] why we are where we are now. You’re really finding the eternal throughlines, from history to now. And it's really beautiful to read that.

I wanted to ask though, about writing a book like Queer Devotion — this is not first book material. This is a book that is so clearly born of years of experience. Years of contemplation. And I wanted to ask what the journey, however roundabout, may have been, was to land on this as a project.

CCB: It has been a long journey. I'm going to try not to give you my entire life story here, but.

*both laughing*

Like you, I was raised in the church. I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, and I was raised mostly in the Methodist Church, so not evangelical, but it was still very conservative, you know? One of my earliest core memories is of sitting in church and being like, I don't believe in this. Like, I don't believe in [the] version of God and of spirituality that was being taught to me. From a very young age, I was like *skeptical sounds.* Does Jesus love me?

From that age, and I feel fortunate for this, I feel like I've always had a pretty firm sense for what I believe is right and wrong and just and equal and none of [that kind of Christianity] ever made sense to me. Eventually I started looking elsewhere for what I could believe in or for beliefs that would reflect my heart back to me and that weren't trying to put me and everybody else in a box and bend us to a will.

When I was in elementary school, I got very into mythology, like super into mythology, and was writing alternate Greek myths and stuff in 4th and 5th grade. Later in high school, I experimented with Wicca. [This was] the early 2000s — core Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Charmed. My favorite movie was The Craft. I bought every Wiccan book that I could afford and find from the bookstore. Hid them in my bedroom along with a tarot deck. That was cool for a while, but it eventually didn't gel either, because the god and goddess thing in Wicca also struck me as wrong because — and at that time, I didn't know that I was non-binary, I didn't know that I was trans. At the time I thought I was bisexual, and I am bisexual, pansexual, whatever. Just not only straight. And the binary heterosexual God and goddess thing struck me as weird, because I was also like: we're talking about god. Why are we making divinity into a human binary gender? Do we really think that the divine can be quantified by sex organs?

So that struck me as weird and wrong, and also the stereotypical gender norms that are applied to the roles of the god and the goddess. And even if we get into maiden/mother/crone territory, just rooting that entirely around the reproductive cycle. So then I became an atheist for about ten years.

JK: I was going to ask if you had an agnostic/atheist state. So that is interesting.

CCB: Yes I did. During that time I was like, am I an atheist? Am I agnostic? I think probably during that time I said I was an atheist, but I think there was always part of me that was believing in something else, just not knowing what it was and not feeling confident enough to try to put words to it, you know?

Then in my late twenties, because of a group of friends that I had met at a reading I was doing, reading a short story in a fiction reading series.

I was reading — it’s a weird story. I was reading a short story about a mother who dies, [and] in her will, she wants to be cremated, and she wants her children to eat her ashes. It’s about how her six different children choose to consume their mother's cremains — which is, by the way, the word for cremated remains is cremains. They made a portmanteau. [Note from Jeanna: Read Charlie’s shorts at PANK here!]

JK: I didn't know that. I love this. I would read this.

CCB: You can. It's on the internet. I'll send it to you.

I think it was the first fiction publication I ever had, [and it was] published by none other than Roxane Gay, when she was the editor of PANK. I got my first acceptance letter from Roxane Gay.

JK: Do you have it framed?

CCB: I mean, I should!

But yeah, a friend — [then] a stranger — came up to me after that reading and was like, so I had a friend who was a chef who died, and I was like, I'm so sorry. And she was like, is it safe for me to eat his remains? And I was like, do not attempt this at home.

JK: You're like, this is fiction.

CCB: I'm not a doctor or a nutritionist or whoever could answer that question for you. So I'm going to go with probably not, but you seem interesting! Let's talk more.

So we became friends. She’s a pagan, and [so] I was like, tell me more about that. And [through] her and a friend group that she introduced me to, [I] started experimenting with other ways of believing. I started getting curious again. Eventually, [I was] identifying as an agnostic pagan where I was like, nature stuff makes sense. Maybe. Maybe there's gods.

I started paying attention to the world again, and I'd been shut down for so long at that point. Not just because I had gone full atheist or agnostic-atheist, but I'd also shut down my queerness, like my exploration in that way. Back in college, I [had] decided that it would be too hard to date women and be queer in the world. So I was like, so I'm just gonna date men. That seems like the easier thing.

That was not the easier thing.

JK: You're like, reader, that was not it.

CCB: No. Forcing yourself to go against yourself and your truth is not the easier thing. I had ended up in an abusive marriage partially because of that, because I made myself so small. I’d kind of actually given up on love at that point? I was like, love is just like mutual toleration, I guess?

JK: If that ain't the straightest thing I've ever heard right there.

*both laughing*

CCB: But when I met these friends, I came back into spiritual curiosity. I also started reading tarot again. At that point, I had stopped believing in anything, including myself.

And then I started doing those things again, and it was like I was waking up after a long sleep. I realized pretty quickly that I was miserable in my life and that I needed to make some changes, and then realized one of those changes was getting a divorce. So I did that. And from there, everything in my life bloomed. Just fucking exploded in the best way. Met my current spouse. Fell in love in actual love and was like, whoa, this is what this is what they write songs about.

Not the first time I'd been in love in my life, but the first time that I was really fully experiencing it and in a way that my heart was open to myself at the same time as another person. I think in previous relationships, I wasn't really able to be fully in it because I was holding part of myself.

I moved across the country, started reading tarot professionally, eventually made my first tarot deck, which also happened by accident.

A lot of that has been a ton of self-inquiry, a ton of reflection and thinking and exploring and contemplating. Like I said, I was into mythology in elementary school. That interest in history has never left me. And so, digging into the past, digging into what people believed before our options became so narrow as today has been a really beautiful source of discovery — of discovering other possibilities that today, [are shut down by] mainstream religion and also to some extent academia and science. It comes at us from all sides: if you believe in anything you're stupid, or if you believe in the wrong things, you're going to hell, you know?

So peeling back the layers and exploring what else was once possible has been a huge source of inspiration and connection for me.

JK: Even in the subtitle of the book, Spirituality Beyond the Binary, it so speaks to [this theme]. There’s obviously a lot of exploration around gender and other binary things [specific to the queer community, in the book], but even what you were just saying: that between religion and science, there is such a allegedly binary way of thinking, at least in the 20th, 21st centuries, which is wild, too, when looking at history and being like, oh, all of these scientists like Isaac Newton were super into weird shit and super into the divine and didn't see it as separate. It’s such a post-enlightenment bifurcation that does so much harm.

CCB: Absolutely. The Cartesian dualism of it all.

I see this, when I sort of abandoned myself for a decade and decided to try to be straight and decided that I believed in nothing. I also, for most of that decade, could not write a thing like. Actually, that's not totally true — I went to grad school during that time. But when I exited that, after I graduated with my MFA and was back in the real world, I met my ex-husband pretty soon. And I could not write a freaking thing. Almost no creativity happened for about six years there.

Then when I started exploring spirituality, tarot magic, belief again, I started exploring myself again. That’s when the creativity came back, and then it exploded in new ways, too. So not just writing fiction, but writing nonfiction and illustrating tarot decks.

So I think that there's also a connection, a through line there for me with spirituality or at least like spiritual curiosity, queerness, and self-acceptance and creativity.

JK: I love that you're articulating that throughline between those things because I want to ask whether in this moment, in this specific project, how that relationship between spirituality and creativity [works].

Although on the surface it's like, oh, you wrote a book — creative — about queer devotions — spiritual. Seems obvious. But I want to ask how writing this particular book changed, deepened, shifted your practice.

CCB: For me, uh, writing this book in itself was an act of devotion. From the very beginning. I was like, I'm undertaking this thing, and it is devotional for me.

I just feel really fortunate that I got to do that and spend a year diving into this so deeply, also get paid for it.

So in the book, I talk about deities and entities, folkloric figures, that I don't work with in a devotional practice. So every entity that I mention in this book is not necessarily who I'm directly working with all the time or who I'm devoted to. But they are still facets of how I perceive of the Everything. Like a capital E. And in writing this book, I really got to explore each of those areas in a deeper way than I had been able to before, especially when I go into Percival and the Fisher King or Gawain and the Green Knight.

JK: The breadth that you cover is so impressive. Like, obviously, you cannot cover, like, worldwide — that would just be like an encyclopedia, at that point. But even within the scope of a reasonable 200, 300 page book, you have a very impressive breadth that you're covering.

CCB: Thank you. And going into these areas that aren't classically deity, right? I've got chapters on Aphrodite-Venus, Dionysus, Joan of Arc, Loki and Odin. But I also have these folkloric sort of literature figures as well, because for me, part of queer devotion for me is not just being devoted to queer Spirit, but being devoted in a way that is queer. Like queerly. And part of that, for me, is looking for the divine in non-traditional, perhaps unorthodox areas.

Because they're everywhere.

JK: I mean, it's a rejection of orthodoxy and a rejection of the very Enlightenment emphasis on, well, if we don't have written text... Your discussion of folkloric, historical, legend, myth, so many things that are passed down orally that are in the current mode of thinking outside of well, what's your source? What's your citation?

CCB: Bingo. In that I'm also sort of walking another — or maybe not walking a tightrope, but negotiating another supposed binary between scholarly standards of proof and evidence and complete rejection of academic inquiry or evidence at all. I think that either extreme holds dangers.

JK: 100%. I was talking with [my wife] Meg and our friend Bee on the podcast recently about imposter syndrome, but specifically regarding the question of verifiable quote-unquote expertise vis a vis the unverified personal gnosis and the dissonance that can arise, which is exactly what you're what you're articulating.

CCB: We’ve seen a lot of criticism toward the academic and toward the scholarly in recent years, which in some cases has come from far right areas, as we're seeing right now, and in other cases have come from far left areas. And some of the criticisms are valid. I have some criticisms of it. But see in that the dangers as well, because if you just start rejecting anything that is evidence based, then you can just make shit up in negative ways and then enshrine it as truth.

JK: And enshrine it as The Order of the Golden Dawn.

CCB: Or enshrine it as The Cass Review, the anti-trans, junk science, politically motivated, quote unquote scientific review, designed to deprive trans people of care in the UK, which we're going to see here in the US shortly.

So in writing this book, I was also negotiating this tension between those two poles because I actually had this really dark moment, a dark night of the soul moment, where I got really deeply depressed because in all of the research I was doing, sort of following these threads of what I saw as queerness or hints of transness or gender identity in history and myth. I kept coming up against scholars who would find various ways to shut that down and say that that was not true. For instance, scholars who argue that Sappho wasn't really a lesbian. Um, Sappho?! The mother of lesbians! Where the sapphic comes from! Scholars saying that she was not a lesbian, because it would have been, like, too hard to be a lesbian back then?

*here, Jeanna breaks out in a hag cackle*

CCB: Exactly. The cishetness of that thought process is astounding, because as we can see right now, just because it is hard to be gay or trans or queer or non-binary does not mean you stop being any of those things.

Their assumption there is entirely based weirdly in, people get to either choose their orientation based on what's most societally expedient at the time? Or like, I don't freaking know.

JK: And even just the two of us speaking — two people who have survived abusive marriages to cishet men. We’re both queer as fuck. Like the way that queerness can exist within those [oppressive] systems is just never accounted for.

CCB: Absolutely. Absolutely. What has happened throughout history is that evidence of queerness — when it happens in societies that are hostile toward queerness — is forced to go underground. It doesn’t stop existing. It just happens out of the public spotlight.

JK: It was underground here in the US in living memory. There is living memory of a time when it was still underground here.

CCB: And for a lot of people, it's still unsafe to be out here in the United States.

And then in other cases where homosexuality has been more accepted, such as in ancient Greece, ancient Rome, scholars will come back to that later and sort of reverse engineer it and be like, oh, actually all of these guys back in ancient Rome who were giving each other handies in the baths weren’t actually gay — it was a power thing. It was how older men had more power over younger men. And I'm like, dudes.

*both laughing*

JK: Fellas, is it gay to give your bestie a handy?

CCB: Like, okay, we’re telling on ourselves a little bit there, aren’t we. Or for instance, where evidence of transness and also spiritual transness or divine transness existed, such as in the priestesses of Cybele or Inanna or Aphrodite, even, had some gender transgressing priesthoods.

The priestesses of Cybele were assigned male at birth. When they entered the priestesshood of the goddess, they would take on traditionally women's clothing, makeup, hairdo. Some of them also ritually castrated themselves. They essentially, for all intents and purposes, lived as women. And this priestesshood lasted through the first two or three hundred years of Christian Rome. Some of the [early] church fathers write screeds against these gender transgressing priestesses. And what happens there is that basically that history gets buried. So either the evidence of queerness has to go underground to exist, or even when it's happening above ground, it then becomes first demonized — literally declared to be satanic, basically, exterminated, and then later just basically wiped from the history books so that it becomes so hard to find.

And even if you can find it, then there's scholars writing about how it didn't really exist or it wasn't really queer or we can't use the word trans to talk about it because it was two thousand years ago.

JK: It’s so much circle jerk equivocating.

I love that you were talking about this because it really gets into actually, one question I did have, which is how you stayed grounded while taking on a work of this immensity. You write with great humor, but I think that folks may not understand how intellectually rigorous this book is. You’re doing some deceptively heavy philosophical work around the body and the spirit, and that Cartesian dualism, like you were saying, and the erotic.

I'm thinking especially of the last chapter of the book where you just go in on the Christian theology, and it's amazing. I was just screaming with delight. You get really into the philosophy and the implications around, like Mary's quote unquote virginity or Jesus’s buried eroticism. And it really is just such an intellectual offering, I think, as much as it is a spiritual offering in that way that, as you're saying, they get to coexist, actually.

But I wanted to ask, because it is an immense project, how you grounded yourself, how you touched grass.

CCB: Well, first of all, thank you.

Writing this book was, like I said, at times really difficult, especially when I had to come face to face with the ways that people like me have been erased and literally exterminated and eradicated in the past while we were also seeing this happen in real time in the United States and elsewhere in the world. Queer history and trans history and literal trans existence is being erased in the United States right now, where they've removed mentions of trans people from freaking Stonewall — like, we’re seeing it. We're living through it happening again.

So that at times was really difficult and dark for me. But also at the same time and for the same exact reasons, really bolstering for me. Really hopeful for me, because I'm here in the 21st century, and I'm not alone. I've got lots of really great company of scholars and writers and theorists and librarians and high school teachers who are like, digging into the history and resurrecting these stories that have people have attempted to bury. And I know that that will happen again, you know? I know that this will rise again.

It almost in a way parallels some of the other rhythms that I talk about in the book, of the mystery religions where initiation involves going into the underworld. Into the self. Into the soul, into the unknown, into fear. And then rising again out of that more resilient, more determined, more connected.

Working on this and being in it with all of these people and entities from history who are still present now. Everything that we talk about as a god or a goddess or a saint — none of them are really dead. They just take on new forms. They go back underground and then they come up in another form somewhere else. This is also historical. This is how gods morph over centuries and locations from Inanna to Aphrodite to Venus to the Virgin Mary. Osiris to Dionysus to Jesus. We can track these rhythms, and that will happen again. We can’t be exterminated. Our stories won't be exterminated.

And getting to write about these stories and publish them and put them out there in the world at this moment in time, for me, is an act of resistance. And it's an act of devotion. It's an act of devotion to everything that I write about in the book and to living queer and trans people right now. To be like, we’re still here. We're not going anywhere. We're not going down. Things are going to be hard. We're going to have to be tough. But we can't be eliminated.

JK: You can't eliminate something that is so essential to the human condition.

CCB: There was a fire behind it. It wasn't just an intellectual exercise. It wasn't just spiritual contemplation. It was a fire of necessity. And a kind of fuck you to the autocratic fascists of the world. Just be like, yeah, I refuse to go quiet.

JK: I have, like, two more questions I want to ask. And one of them is a little bit personal. I don't want to spoil the book for people, but also, there are a lot of activities and rituals and appendices. We’ve been talking about sharing stories and the historical work and research that you have in it. There's also so much practical application for folks that I really want to flag so that they know that this book is really a companion. It’s a friend to your spiritual practice.

On a personal note, I was really moved by your Queered Rosary, which is in an appendix at the very, very end. Like you, I didn't grow up Catholic myself, but my dad's family is very Catholic, and my grandmother basically lived with us for most of my adolescence. And so I have a weird, complicated kinship — like, I’m not Catholic, but I've been to mass so much I can do the service in my sleep? That’s just to say that saying the Hail Mary and praying Psalms is an increasingly large part of my own ancestral practice, and so having this queered Hail Mary was just such an extraordinary gift. And you do share in that section that you have also reclaimed some of the Catholic prayers, as it were, as part of your own ancestral veneration.

And I wanted to ask, like you already mentioned — you're like, don't get it twisted. Don’t think that just because I'm writing about these spirits that I'm personally devoted to all of them. That is such a tender thing to navigate when you're a public person and you have private spiritual devotion. So I wanted to ask how you decided which things to share in the book in the first place, and how you approached that?

CCB: For clarification, I do see myself as in relationship with everything I wrote about. But it's not like I have a Sir Gawain and the Green Knight altar, or that I pray to the Fisher King. But they are present in my gnosis. They’re almost like keys or doorways for me, that lead to a greater understanding of everything.

But as far as the queered rosary that I provide. So my main bestie is Venus, Aphrodite, Mary. It’s her and it's Dionysus. Those are my main two which I think that when people read the book will become obvious at a certain point.

So my devotion with — we'll just call her Venus-Mary for short — came to me as a total surprise, because I didn’t consider myself a Christian from a young age. I went so far from the church and because of it, I'm also still incredibly distrustful of organized religion. And I never liked Mary growing up because she was only ever presented to me as a breeder, basically. And then she just disappears from the picture, put back into the closet with the rest of the nativity scene, and doesn’t really feature in the Protestantism that I grew up with.

But at the same time, I was always fascinated a little bit with the Catholic Church. There was a church near our house, Our Lady of Sorrows, and I never went inside, but there was a big statue of Mary right outside of it. I would pass it all the time, and that always just wowed me because like, there's a woman right there, front and center. Which was so different from the very just male oriented, male dominated church that I grew up in. Of course, the Catholic Church still is male oriented and male dominated, but that always was tantalizing and interesting for me.

Once I figured out that I was non-binary, I found myself unable to engage with goddesses or feminine images because it felt dysphoric for me. I was trying to get away from being feminized by the world, and so I found myself unable to interface with those energies. Also, gender just doesn't make sense to me, period. So, like, I'm non-binary slash agender, you know? Like, what even is it? Like who cares?

But nonetheless, I was still like, okay, I can’t do goddesses. Then I had top surgery in 2022. And it was a like magical, like miracle almost level sort of thing for me.

I thought [getting the surgery] would be small fry. I never was so dysphoric that I was just abjectly miserable. But I decided that I deserved to get top surgery because it would improve my quality of life.

JK: You don't have to be in the deepest suffering to deserve —

CCB: Precisely, precisely. So I got top surgery and [when] I woke up from anesthesia, the first thing I did was start crying happy tears. Afterwards, I remember being on the couch, my chest still completely wrapped up, and feeling my child self, like at the foot of the couch, kind of hovering over me and then coming back into my body somehow. I had never been able to touch inner child work because it was just too much. I had to hold that away with like a ten foot pole. But after top surgery, it was like the inner child in me just filled with joy. It was like I was back, like I came back.

And with that, all of a sudden, I was also able to work with goddesses and be interested in these more traditionally feminine things. I'd been having Mary kind of show up to me in all these different ways after that for a little while. Just tiny little pings [that I ignored]. I've still got Christian stuff that needs healing, you know.

JK: It's the gift that keeps on giving.

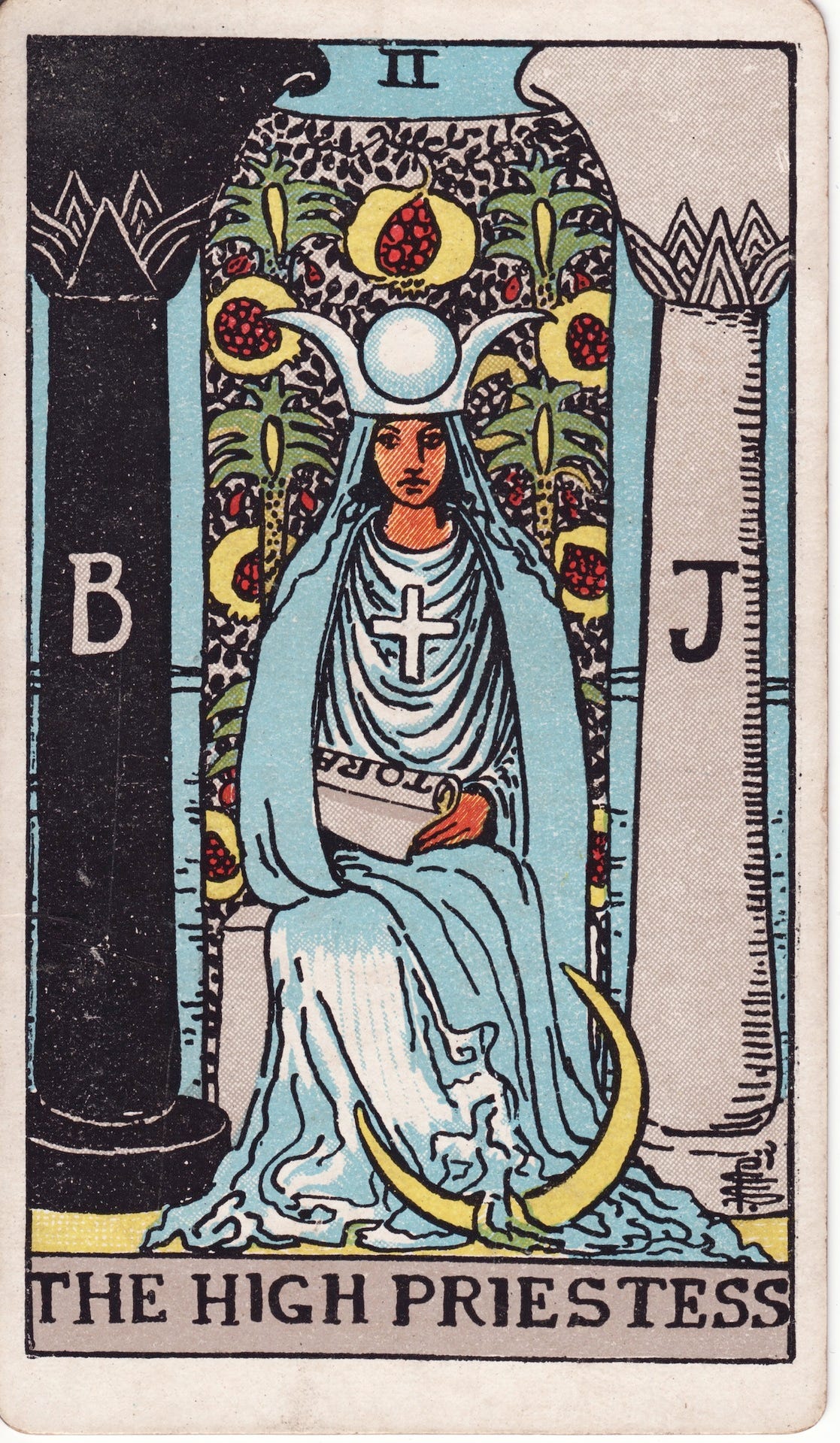

CCB: And then my partner and I were in a thrift store, like a big antique mall thrift store, and saw this statue-fountain of Mary. I saw it and was like, high priestess. It's a statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe, which is standing on a crescent moon. Which is basically what we see in the Rider-Waite-Smith High Priestess.

And I was like, should I get this fountain? No, I don’t want a fountain of the Virgin Mary in my house. Left. That was before top surgery. Came back three months later after I had top surgery. The fountain was still there.

JK: Waiting for you.

CCB: Yeah. I was like, she's coming home. Took her home, washed her, scrubbed her. Got the fountain working again. Put her over here by my window on my altar. And then just kind of felt it out from there.

When I looked at her, I was like, okay, we've got the Virgin Mary, but we've also got Aphrodite, Inanna, Ishtar, Isis — all of these goddesses that were historically syncretized and bled into each other and informed each other. Not just a, I’m looking back at it and making connections. But literally at the time that’s how it worked. And then aspects of these goddesses were historically wrapped into the Virgin Mary, especially her iconography, and also in some of her stories. Same thing as how some aspects of Jesus and his mythology came from the mythology of Dionysus.

But on a devotional level, I just started figuring it out. I was studying the Orphic hymns, and so I read the Orphic Hymn to Aphrodite out loud to her. I would sit by my altar and read Sappho — Sappho's hymn to Aphrodite. Which is also, by the way, a spell.

I can't remember how the rosary thing happened. I just started reading and researching the links that I kind of intuited between Mary and these goddesses that existed before. In that research, I was reading Clark Strand and Perdita Finn's Way of the Rose, which is about the rosary. Got myself a rosary. Around that same time, found Jonah Welch online, on Instagram, [who] does a queer trans rosary practice. So I started praying the rosary and rewriting the traditional prayers to it. Through that, also felt myself connecting to a side of my lineage that was beforehand mostly unexplored.

The rosary to me is kind of like shuffling tarot cards, with this tactile element to it as well. It brings me into a meditative kind of relaxed space, and so even that alone is a sort of grounding, mindfulness practice. Getting to rewrite those prayers and queer them felt at the same time healing, and also subversive as hell.

I was a little bit afraid of getting smited, you know.

JK: You’re like, does the Old Testament God still do that? Does that still happen?

CCB: I was like, I don't believe in this. I don't believe that that will happen. But that old part of me that was trained to be so afraid of anything that could be devilish or heretical.

But one of the first times that I actually prayed the rosary, I had this wild experience where I started crying, which I was, like, not prepared for because I went in with just curiosity. Like, I'm just going to try it and see what happens. And then just like, cracked open and just wow. Tears streaming down my face. I had my eyes closed, and it felt like fingers were touching my face. The tears felt like fingers were tracing their way down my cheeks, which just made me cry more. It was so lovely.

It felt like coming full circle, somehow. Reconnecting to a point that maybe once upon a time I had had this spiritual connection in myself as a young, young kid that was then trained out of me by the institutional religion that I grew up in and then stomped out by the forces of the world. Then I was afraid, you know, to do it for so long. I couldn't connect with anything that was traditionally feminine, even if I think that gender is bullshit. It felt like coming full circle and like being reunited with myself.

Enjoyed this interview? Pre-order Queer Devotion! And be sure to subscribe to Charlie’s newsletter here on Substack,

.

I need a copy of this book! Also, loved seeing a reference to Perdita in here. Her daughter, Sophie Strand, who is also here on Substack, is queering our understanding of chronic illness and the body in the most moving way. Definitely check her out.

Thank you so much, Jeanna! For this conversation, for reading my book with such thoughtfulness, and for blurbing it too. Talking with you was a total joy and, frankly, an honor! 🥰