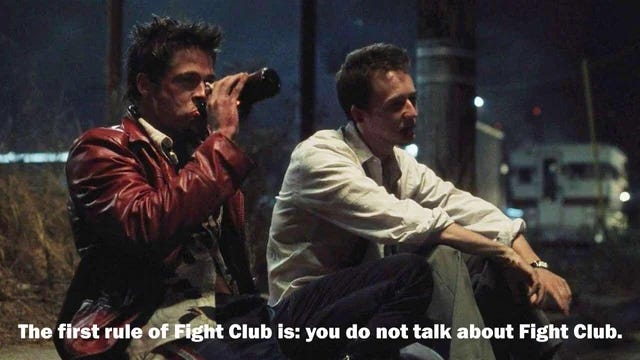

the first rule of going out on submission is

& also on publishing & white civility

astrology for writers is a labor-intensive, exclusively reader-supported publication. if you enjoy getting this newsletter in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

also — the newsletter is on its annual birthday sale for the next lunar cycle!

The first rule of going out on submission [with a book] is, we don’t talk about going out on submission.

But fuck that rule and the white civility that undergirds it.

My agent and I are going out on submission with my next book (which itself is based on this newsletter) very soon, and in celebration of that (and also because I love talking about the business of publishing), I wanted to write about going out on submission.

Some wonderful folks in the Astrology for Writers Discord asked questions to help guide the “WTF is submission” explanatory part of this missive, but I also wanted to dig into the overarching issue of “professionalism” that dictates silence around this vital part of the publishing process — and question who that silence benefits and who it really serves.

But first: let’s define our terms. What is submission, you ask.

It is the part of the publishing process where, having spent months or even years working on a book or book proposal with your agent, your agent goes out like a medieval peddler and brings your book to the respective courts of publishers, trying to hawk the goods. Is my terrible metaphor for the experience.

Being on submission / “going/being out with a book” is basically the awkward phrase for “trying to f—ing sell my book.” This is when your trusted agent sends pitches to anywhere from one to several dozen editors, trying to get them interested in buying your project. This process can go very quickly — these are the, my book sold in 48 hours at auction stories. But more often than not, the process is terribly slow. Far more often than we are told, the process ends in failure — AKA, a book not being sold at all. More on that later.

That list of editors the agent is trying to sell to is called the Sub List: the list your agent has compiled of editors at different publishers and imprints that your book will be submitted to for consideration. This will likely include a lot of Big 5, meaning the five largest English language publishers — HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, Penguin Random House, Hachette, and MacMillan. But I want to stress that there are so, so many publishers to submit your book to who are not Big 5 and who, depending on the kind of book, may actually be such a better fucking fit for your project. W.W. Norton, Bloomsbury, Scholastic, Sourcebooks, Abrams, Graywolf, Tin House, Sounds True, and Chronicle are only a few of the well respected, medium-to-largeish size independents who will often, depending on genre and category, be on your list. Then, you have the specialty indies of varying sizes. And those specifically niche indies can really work for you — Entangled, a romantasy indie, publishes Rebecca Yarros, whose Onyx Storm just became the fastest selling adult fiction in 20+ years.

But I said imprints and publishers. What does “imprint” mean? Your agent is not just going to submit to “Simon & Schuster”; she’s going to submit to multiple editors at the mini-publishers (aka “imprints”) within the conglomerate that is Simon & Schuster to see if any of them are interested in the project. It bears noting that some imprints (Bold Type, Hay House) were literally once independent publishers that were acquired and absorbed by the parent company. Within a year of having initially sold my debut to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, the company was bought by HarperCollins and became the “Mariner” imprint. So it goes.

Imprints usually specialize in a particular genre or sensibility — the aforementioned Orbit at Hachette is their sci-fi/fantasy imprint, which publishes one of my all-time favorite writers N.K. Jemisin. Fans of literary fiction are probably familiar with names like Knopf and Riverhead, which are actually both under the PRH umbrella.

The tl;dr here is that there are so many imprints. (And this isn’t even getting into the “rules” about which imprints at specific publishers are allowed to bid against each other.) General rule of thumb is, you only submit to one editor per imprint. And this is what that sub list is: a list of editors at every imprint and/or publisher who may be interested in your book.

Why, you ask, would your agent know that such and such editor is interested in your book? (But really, someone in the astro for writers discord did ask this.)

That editor publicly acquires books in the same category / with the same topics as yours. (Publisher’s Marketplace is the most public-facing database where you can search by keyword/author/genre/category, all for $25/month — a fee I gladly pay when on submission myself.)

Your agent asked around in their own network and heard that the editor might be a good fit for your project because of XYZ reasons. This industry is, truly, so so small.

Your agent has a friendly relationship with that editor and keeps all kinds of notes about their special interests and backstory in a murder book (that queer editor grew up in Ohio, too?! And your queer rom com is set in Ohio?! Wild! WHAT A COINCIDENCE THAT YOUR AGENT WANTS TO SEND IT TO THEM HOW ODD THAT SHE KNOWS SO MUCH ABOUT WHY YOUR BOOK MIGHT RESONATE WITH THAT EDITOR).

I truly cannot stress the value of #3. That is the whole reason to have an agent in the first place — that your agent is friendly with slash friends with editors and can soft pitch your book to them well before you’re actually out in the world trying to sell it. I know for a fact that my agent soft pitched a number of the editors we went to with Heretic well before the official pitch landed in their inboxes, that they were already interested and already curious about the project. There’s an art/science to making sure that the editors you’re most hopeful about aren’t just getting a cold pitch in their inbox. Or so I hear.

However, even the friendliest, most well respected agent is probably not friends with every single editor at every single publisher, because it’s 2025 and we don’t have the time or energy for endless catch up dates with people we’ve met twice. Your agent is also less likely to have a personal relationship with every single editor you’re submitting to if you, like me, write in a bunch of different categories, which ngl is hell for your career means that you’re developing profoundly different sub lists for different projects. A lot of editors acquire across category and genre, but typically, the editor and the imprint will trend more literary or more commercial, for lack of a better delineation. (And an imperfect one, but.) My first book, Heretic, was memoir, so narrative nonfiction (with footnotes), and was more firmly on the literary side (the first time out on sub, we submitted to places like Riverhead). My hopefully second book, based on this newsletter, is prescriptive nonfiction, and decidedly on the commercial side of things. I don’t know every imprint/pub we’ll be submitting to yet, but I can say with absolute certainty that we will not be submitting an astrology book to Riverhead.

This brings me to a thoughtful question from a Discord member, which is: do agents appreciate writerly input on the sub list, or are they irritated by it? The level of collaboration on the sub list depends on the nature of the relationship between agent and author. It’s also a question of how much you, the writer, wants to be involved in the behind-the-scenes business dealings. Plenty of folks just want the agent to say “this is what we’re doing” and wash their hands of the specifics. You can absolutely discuss style of working/collaboration and your preferences with agents when in the query process.

My relationship with my agent Dana Murphy is decidedly collaborative. (Some of you may have even attended one of my annual LGBTQIA+ Publishing Q&As, which Dana — who is also queer — has joined me for.) Some background: when I first signed with her in 2019, she was a junior agent at The Book Group who was actively building her list. I was one of her earliest clients, and we very intentionally, very explicitly wanted to grow in our careers together.

As in any relationship, we’ve navigated some very high highs (selling at auction! a sold out book launch!) and very low lows (not selling at all; my publisher going on strike). We’ve worked on several projects together that we ultimately chose to shelve. Most of all, we’ve learned just how much we can talk business and strategize, but then, both of us have Capricorn moons, and I’m an Aquarius rising and Dana has an Aquarius sun, and so we are prettyyyyyyy obsessed with understanding how systems work. Which very much serves our mutual goals.

I have witnessed how the agent-client dynamic can be extremely different when a writer signs with an agent who is already advanced in their career, especially when they are a very high-powered, their reputation-enters-the-room-first kind of agent. In those cases, it tends to be more of a, “I [writer] do what they [agent] tell me to do” situation (frequently to the writer’s benefit, to be clear, although that power dynamic has its own field of conflict-and-hurt-feelings landmines). So it’s a matter of discernment and preference, although I hope that any agent worth their salt (no matter how high powered) would make use of their author’s network and connections. That’s just good business.

This is to say: do agents appreciate writerly input on sub list / the submission process, or are they irritated? … I imagine that it depends. As the author, you have to ask yourself: is this spreadsheet-making input and research coming from a desire to control, or do I actually have some insight to contribute to the process that my agent (who does this for a living) would somehow not know?

Because I work as an astrologer and read (and write) across occultism, I have a pretty strong sense of which other “mind/body/spirit” (ugh, hate that name) books are in conversation with my own. Based on that, I have a pretty good instinct about which editors might be open to my queer-as-shit, anti-capitalist worldview and which only acquire the love-and-light girlies. That is the kind of info I put in the rather enormous and sprawling spreadsheet I made for Dana this time around.

Because mind/body/spirit isn’t a category Dana typically sells into and because I happen to be very, very steeped in it, with a lot of friends and colleagues who are also authors in the space, we were in a unique position where I actually did have a lot to contribute to the sub list this time around. I have friends and colleagues who are both working on books with Big 5 editors and who have recently submitted to (and been rejected) by those same editors, and so I’m able to put detailed notes about a particular person’s editorial style, or reasons for rejection they recently gave.

For her part, Dana was thrilled with my spreadsheet. Would another agent? Who knows. All I know from this industry is that no one — agent, editor, author — has the complete picture, and all we can ever do is share as much information as possible. A rising tide lifts all boats.

Which is… the whole point of this missive. About how I’m going out on submission for the third time in my career, and how I’m so, so sick of industry conventions which insist that it’s gauche to talk about it.

To be clear, I was never ~explicitly~ told not to talk about going out on submission. I just witnessed friends with books who, upon going out, said “well I can’t talk about it.” I was advised by writer friends to be very careful with who I told I was on submission, because people could get weird. (To be fair, that is true.)

But not talking about being on submission (or strategizing for submission) only serves to keep writers disenfranchised. It purposefully obscures the behind-the-scenes of the industry. How on earth are authors supposed to know if their experience is “normal” or particularly extreme? (Because not all agents are as communicative and thorough as Dana, but that’s a different subject.)

The thing is, no one has a concrete reason for not talking about being on submission — which is so often the case with white civility, the whole “don’t talk about money or how the sausage is made” bullshit. Here are the reasons my decidedly working class brain has been able to brainstorm:

You don’t talk about submission because god the process is so stressful, there’s no timeline, and it’s easy to be overwhelmed by people asking you if your book has sold yet, as if you wouldn’t scream from the rooftops if it had. (As a personal choice, this is so valid.)

You don’t talk about submission because if your book doesn’t sell, it’s embarrassing. (Self-protective, but as someone who has gone out and not sold a book, I get it.)

You don’t talk about submission because editors may see you talking about it, and what if that editor is sent a pitch much later than you were posting about it and so they realize they weren’t in your first round, and they will get butt-hurt about that and reject you for the sin of not wanting them the most. Or something.

That last point about editors “seeing” you be out on sub is what most will point to as the reason for the rule of silence, but it quickly collapses under scrutiny. Which authors — especially debut unknowns — are being followed on socials and newsletter by every single editor on their sub list? Unless you are an objectively huge deal (I’m thinking Sarah J. Maas, Kristen Hannah levels here), OR unless you work in publishing (or book media) and consequently have real, private IG-type relationships with those folks, I sincerely doubt that the average writer is being stalked on social by prospective editors.

Editors are overworked and underpaid and their inboxes are unimaginably monstrous. It’s the height of Main Character Energy to think that an editor who doesn’t know you will drop all of their existing responsibilities to go scroll through your Bluesky to see if you talked about going on sub.

My friend and fellow writers’ group comrade

said this when I asked for her hot take on the topic:My understanding is that you're not supposed to announce when you go on sub because if you end up doing multiple tiers of submissions, editors in later tiers might realize they weren't your top choice (if they see your posts, and are paying attention, and give a shit...). This makes sense I guess, but I also have a hard time following any of the rules that keep this industry and its machinations so opaque and isolating.

And Lilly’s identifying of the “rules” that keep the industry purposefully opaque and isolating is exactly the thing that I want to publicly rebel against here.

There is a quiet, decidedly upper class (white) gentility to traditional New York publishing that operates on a lot of unspoken rules and assumptions about propriety.

This is a gentility that is designed for insiders to identify each other, and consequently to keep the riff raff out. (I talked with Jenny Xu, my editor for Heretic, about this at length a few years ago.) If that sounds extreme to you, consider how many authors are still rejected by editors saying things like, “We have our gay/trans/Black book for the year.” I can think of two friends, off the top of my head!, who have received those verbatim rejections within the 18 months!!!

(And if you think that that kind of statement/sentiment isn’t gonna skyrocket in lieu of the ~current administration~ whew do I have news for you.)

The culture of silence in publishing silences authors’ ability to better advocate for ourselves.

When we are treated like we should already know the inner workings of a deliberately opaque (and antiquated) industry.

When we are told to be quiet because we can’t possibly know any better about our worth.

When we are dismissed on basis of our identity.

When there is such alarming disparity in author pay (and contract terms) across category, and sometimes even within the same publisher.

Then yeah, it really is our business to talk about what we’re selling, when we’re selling, and what kind of feedback we get.

Not talking about how hard it is to sell books doesn’t actually help our careers. It just makes it harder to ascertain industry baselines, harder to know what to ask for, harder to figure out which editors already got their “gay book” for the year. And so on.

But that’s not professional, some say. “Professionalism” is itself a construct of white supremacy, an assumption of what constitutes proper behavior that is usually coded as middle to upper class white. Talking about the terms and conditions of our contracts is, apparently, not “professional.” See also: conversations about salary transparency and just how much effort employers go to prevent it from happening.

Here in the US, we are in unprecedented times. I don’t think it’s frivolous to be selling a book. I think we do what we can, where we are. And I think that means confronting the vestiges of white supremacy in the publishing industry.

One very concrete thing we can do, as authors who are traditionally published, is to de-mystify the unspoken and talk about money. We can tell our fellow artists, which is to say our fellow workers, what we are bargaining for, so that we might all bargain better together.

I want to be clear: not every book sells to a traditional publisher. Plenty of submissions fail. I’ve had one such failure myself (which I have already written about plenty and so will not repeat here). And some books are just bad — not well written, ill researched, etc. You’ve read them. I’ve read them. Plenty of books I believe to be bad are published, so it stands to reason that plenty more are rejected. But this also means that plenty of good books, or at least books I would absolutely want to read, are also rejected.

Just because a publisher acquires a book doesn’t mean that the book is “good” — it just means that they think the book will sell. We have to separate the morality, or taste, from the business.

It is a main project of capitalism to put the onus of failure on the individual’s effort rather than the system they work within.

Plenty of books don’t sell. And yet, the market continues to grow. If editors are being deluged with pitches, then agents’ inboxes are out to sea. At a certain point, we have to question whether the industry — which is funneling more writers than ever in, while major houses are tightening purse strings — is, perhaps, at least somewhat to blame for the landfill of busted egos and abandoned careers it has wrought.

I want to leave you with this: if you go out on submission and your book doesn’t sell, please know that that is so, so normal. Increasingly normal, actually. Especially if you are queer, if you are a person of color, if you are disabled, if you come from and are writing to a rural and/or working class community — please know that the burden of proving that there is a market for your project is unfairly on you and your agent.

We need to talk about going on submission, because we need to know what kinds of books are trying to get out in the world. And we need to keep talking about going out.

Whether or not the book based on the newsletter sells, I’ll share more details once we’re on the other end re: which publishers, we went to, what the timeline was, and what the rejections said, etc. Transparency!

In the meantime, feel free to share your own stories in the comments. While they are usually limited to paid subscribers, I’ll be leaving them open on this post so that folks can connect.

Because I am (obviously) committed to industry transparency, I am not paywalling this post. However, this newsletter ~is~ how I pay my bills, and annual subscriptions (which come with Discord membership) are currently on sale, if you’re so inclined to support:

Thanks for writing this! I'm currently on submission for the third time. The first was one of those sold in a week at auction stories, which was a real mind-f**k when you later realize that's probably as exciting as it's ever going to get. The second book did not sell. And here I am hoping to sell a third, with a lot more knowledge of the market, who all the players are (I write for kids, which is a much smaller market) and a heavy dose of reality that borders on negativity, haha. I wish you luck with your next submission!

Amen, sister! As someone who has been published twice by a Big Five, I still recall how gobsmacked I was when first told by an inside-publishing partner, as though I was clueless, "Writers never get paid anything!" And I replied, "and that's supposed to be motivating for me?"