we fight with daddy: garrard conley in conversation with jeanna kadlec

two queer ex-evangelicals talk (writing about) religion and sexuality

The first time I met Garrard Conley was blink-and-you’ll-miss-it brief. He was a scheduled guest on an ex’s podcast, and I insisted on coming along to the studio to meet him. I’ll be so quick, I told her. I’ll just say hello and thank him for his work and leave.

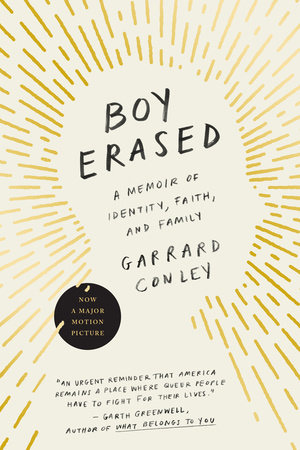

Which is what I did. I had read his first book, the searing memoir Boy Erased which details his time in conversion therapy alongside his evangelical upbringing. To say it moved me deeply is insufficient for the impact it had on me. At the time, I’d never before read a book by another queer ex-evangelical. It also inspired me to further commit to my own project: at the time, Heretic was an idea I worked on only occasionally.

I tell Garrard this in our conversation here, but it’s true: there is no Heretic without Boy Erased. Arguably, there are far fewer — if any — memoirs that reckon with religious themes in recent years. Publishing notoriously requires comp (comparative) titles from books with similar projects that have done well in the marketplace. Boy Erased has held the door open for many of us.

Holding the door open for those behind you is an attitude that Garrard embodies, period. Garrard is known for his generosity in the literary world; whereas sometimes folks can become more withdrawn towards up-and-coming writers the more success they have, Garrard has only become more present. Even though he’s also an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Kennesaw State University, he still extends so much of friendship and goodwill and time to so many up and coming writers.

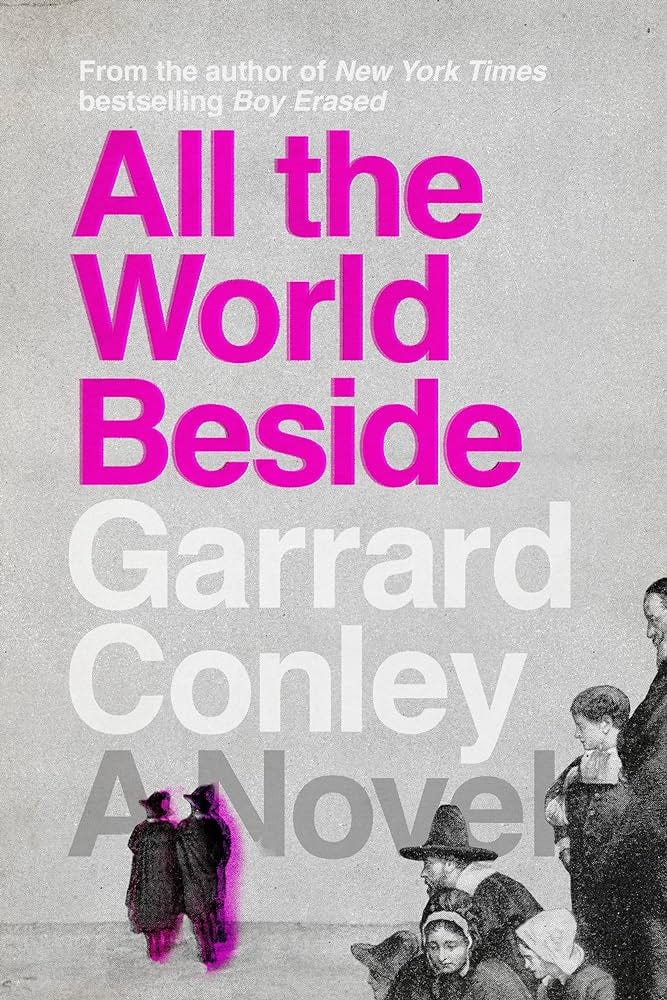

This is all to say. Talking to him for the newsletter was a no-brainer, especially given the decidedly religious themes of his debut novel, All the World Beside. It features a love story between two men in Puritan New England, but also so much more. It’s so queer. The writing is gorgeous. I cannot recommend it enough.

Garrard joined me on Zoom to talk about Puritans, representing queerness in a historical setting, the publishing industry, and so much more. I hope you enjoy our conversation as much as I did.

All the World Beside comes out next Tuesday, March 26th.

this interview has been edited for length

~our scene opens with me pulling up his birth chart~

Garrard Conley: I trust you. You’re the expert.

Jeanna Kadlec: *laughing* Okay, what is your birthday? *proceeds to input all birth info into astro.com* Oh, I see. I understand.

GC: I can sense something making sense.

JK: Yes. Aries sun. And then the moon, which is like our emotional state of being but also our relationship to our body and vulnerability, all of that. You have a Pisces moon.

GC: I thought so.

JK: And it's also in the part of the chart that has a lot to do with, incidentally, creativity and pleasure and pursuing things that feel good and really good people. So that's really sweet.

GC: So that's what's balancing out in my Aries, huh? Overthinking and being too emotional. *both laughing*

JK: Then you also have Mercury, the planet in the chart that has a lot to do with how you think, how you communicate, how you write. You have Mercury in Aries, very bold and then communicating in a very direct —

GC: Uh huh.

JK: You know, whatever you say might be in the head, out the mouth. We fire Mercurys learn as we learn as we get older that that's maybe not so much how we want to do things.

GC: We do.

JK: But then also, and I really love this too, your Venus — which is to say, your relationship to love and relationships, but also to art — is also in Aries. And Venus in Aries is like — I see that so much in the charts of activists, but it's also in the charts of a lot of artists who are very trailblazing, genre-wise, and who are very much working outside of convention.

GC: Good to know.

JK: These are things you already know about yourself.

GC: But it's nice to have it confirmed, you know. It puts you back on your path sometimes because you're like, am I? Am I able to do this? Oh, probably. Because that's who I am.

JK: With all of this Aries stuff that you have happening, though, I think that also speaks to how much you've been this singular one who's been out there trailblazing by yourself, having to do it. And a lot of the times without support, which also shows up in this chart, actually.

GC: All the time. All the time. And I've had so much support from so many people, especially in the writing world. It’s an apprenticeship model, really, and it has worked for me, but definitely in terms of getting my story out there and really believing in it, [it’s been solitary].

With Boy Erased and the topic of conversion therapy, when I first wrote that book, there were maybe two states who had bans on the books against conversion therapy. No one even knew what the term was, aside from queer people. Even then, I would talk to older gay men, and they wouldn't know. They would say, oh, yeah, I went through that. They just didn't call it that, you know?

JK: Wow.

GC: I mean, it was phenomenal for me. It was exhausting and also amazing to see how words could actually shape activism and to believe in all of those things again. We get so cynical about how that works. I remember getting an email from a kid named Max, who's now doing wonderfully; he graduated college. But when he was sixteen, he wrote me about just reading my book in a library, because his parents wouldn't let him read it. And he had been suicidal, and he wasn't anymore after reading it.

The book wasn't selling much [then], but this letter came in, and I just go, you know what? All worth it for that. And it still is. But it was lonely for a long time.

JK: Yeah. I think that that's something that so often folks who get to be a first, or are like, oh, my story is unlike any that are out there, don't necessarily understand — question mark — when the book deal —

GC: You understand.

JK: I mean, I do. But even so, I was still lucky because I got to use your book as a comp.

GC: That makes me so happy, though.

JK: I felt so tremendously lucky. And like, I know you know this, but also do you know how much so many of us are like, indebted to you?

GC: Of course, I would never think of it that way, because I, like, hate myself. *laughing*

JK: I know you wouldn't. But also, Heretic doesn't exist without Boy Erased. You know?

GC: That makes me so happy though. It’s also so hard to sell queer women's stories. I know it's ridiculous out there when it comes to that.

JK: Yeah, mine didn't sell the first time. We had to go out with it again. Anyway!

GC: You did it. But see, that's so rare that you go out a second time and it works. So I'm so glad to hear that it did.

JK: But that is to say, you're saying that the worth is in the people who find the story. That the work is life-saving in that sense.

GC: It is. And you already know. All the other things that you get: the accolades, the attention, whatever. It all fades away so quickly. Like you get a thing, and then an hour later, you're like, why don't I have another thing? Why didn't I make that list? Why don't I do this? Why did that person get that? You know, it's like completely fucking insane, right? And it's madness.

But then: real connection. And I think this is true of everything in life, right? We're getting to the spiritual shit now. Everything is actually about connection and love, I think, and remedying those moments when there are ruptures of that. In life, in the world right now, there are many such ruptures. And you don't always know that until you get what you want.

JK: Yeah.

When you get what you want, that's when you understand what actually matters. Because you're like, I could have chased that dream my whole fucking life and still been unsatisfied.

GC: When you get what you want, that's when you understand what actually matters. Because you're like, I could have chased that dream my whole fucking life and still been unsatisfied. But instead, I'm going to focus on family and love and found family. That’s going to make my life so much better.

JK: And it took getting the book deal with Boy Erased and having that experience to circle back around.

GC: Yeah. I think I would have been lost for a longer period of time if I had been eagerly trying to do that. Then, when everything exploded with Boy Erased, and I was able to really have a platform, that was when I learned it makes me miserable to think about that stuff too much. It doesn't matter how much of it you've gotten. Whenever you get it, you're like oh shit. That is wonderful. Love to hear that I've gotten this thing. But now, I'm thinking of myself only as a public figure, and I'm not being real to myself, or I've gotten lost in what it is to be checking Google every five minutes.

I used to hear people complain about that and think they were like entitled assholes — and there is a certain amount to that. When we get things, we want more things. But I do think that it's a truth that everyone can share, which is that all that matters is love.

JK: Is that how you would define your spirituality now? How would you articulate that for yourself?

GC: For so long, I had an aversion to words like spirituality or even love, because they've been used against me, right? Love in Action was the name of my conversion therapy place. It sounds like a bad porn, right?

JK: It does, yes.

GC: So that word was so hard for me to reclaim. I thought my parents loved me, and then they sent me to that place, and I felt betrayed. I felt betrayed by the community I grew up in, the fundamentalist worldview that I know you know so well.

Because I loved those people so fiercely. I felt loved and I felt supported until I was out. Because of that, I learned love in a really crooked way, right? Which is just: I want to return to that. Can you bring me back to my innocence so that people will love me again? [Because] the minute I speak out, they're going to hate me. So I should just shut up.

And I shut up for a long time. I played it off. I would be like, oh, yeah, conversion therapy didn't work, you know? Ha, ha. Go watch But I'm a Cheerleader, which I love. *both laughing* But also, I'm not dealing with my trauma.

I think that my journey as a writer has been reclaiming that love for myself on conditions that feel fair. I'm willing to talk to people who have different beliefs than me to a certain extent. There are certain issues that that's not true with — like, I'm not going to [befriend] a TERF. That’s a line I won’t cross. But I will, maybe in a bar, make an argument with the TERF if they come up and they're willing to have a real conversation. Which is unlikely.

JK: You can tell the difference.

GC: You can.

JK: I also feel like folks who grow up in those really extremist environments — we’re very keen to the difference.

GC: Yeah. And I have this superpower ability to go into those spaces and make them feel at ease and just sort of sneak my lessons in there. Just nudge them. I'm not sure it ever actually works. But they do listen when I'm talking, you know, because I look like one of their sons, right? I look like one of those megachurch people. I kind of keep my look that way on purpose. *both laughing*

JK: You're going for youth pastor coded?

GC: A little!

JK: God, Lyz Lenz and I were talking about that months ago. Like the coded youth pastor shit.

GC: It works, okay?! A lot of these churches will still invite me to places, even though we have totally different political beliefs. I don't do that a lot because it's very taxing, of course. But I do like the ability to sort of maneuver in that world, because despite everything — and I may change my mind on this honestly, after this election — but despite everything, I have to have faith that people can change their minds and hearts. Here’s another aspect of faith. I know that sounds like love is love and all that stuff, which is still fine in my book.

JK: We all start somewhere.

GC: It sounds a little bit like that, and I think I get labeled like that, and I'm okay with that because I'm really trying to do something different.

JK: What do you mean, you get labeled like that?

GC: I think because of the success of the Boy Erased film, which was very different from my book. It had a different tone, I would say. I think people assumed that my politics were shaped a certain way, and that I was a little bit boring, in terms of being a queer person. I always surprise people whenever they meet me, like the things that come out of my mouth. They're shocked.

But I do think there was a little bit of a, oh, is he just going to turn 40 and turn into one of those anti-cancel culture people? I think people were kind of waiting to see if that was going to happen, and I don't blame them. Because a lot of my friends did. A lot of people that I knew have become very… let's just say opinionated about cancel culture. While I agree with some of those assessments — because every movement needs critique, right? the left certainly needs critique right now — I [also] believe that there's always nuance involved in each of these cases. We can’t just blanket statement, the left is going to cancel everyone who's different from their political beliefs. It's just not true from what I understand.

JK: Yeah. That makes a lot of sense. The aging corporate gay is certainly, um, an archetype.

GC: It’s weird. It's getting real weird out there. I used to think it was cute whenever the gay couples would post on Instagram, like enjoying our coffee together! Like, that's fine. But after a while you're like, okay, we're still enjoying our coffee together. It's nine years later. I guess we're just going to document aging gays being happy. That's fine. Great. Love it. Also, not my thing.

JK: I don't really watch awards ceremonies anymore, but what was it that Nick Offerman did? He won for The Last of Us, and he obviously plays a gay man in The Last of Us. In his acceptance speech, I saw queers specifically critiquing it because he did the whole “It’s not a gay story; it’s a love story.”

GC: Oh yeah.

JK: And like, it is gay, though? It is a gay story.

GC: I got some flack for that with Boy Erased because Joel Edgerton directed it. He's a straight man. But the whole team behind it was very queer. I think what I was most frustrated with in that whole situation, which can tack more directly onto Nick Offerman, [was] when people came after Lucas Hedges for playing me. I was really upset because I knew Lucas, and I knew he wasn't straight. He came out very briefly in some sort of article to make it okay when the promotion was going on, but he sort of had to. I thought that was a minor tragedy, because I felt really protective of him. He's a very sweet person. A truly genuine person.

I just thought, really? Do we have to do this to young actors? Like, I get it when they're a little older, maybe you question that. But you don't know his personal life. He's not that public with his life. So that was really frustrating to me, all the Brooklyn queers yelling about that. I was like, I get representation matters. Obviously. I care deeply about that subject. That's central to my work and my life. And I wouldn't have worked with Lucas if I didn't think that he was the right person.

We get a little one sided on things every now and then in our community, as you know.

JK: Do you find that — and I know that you don't live in New York anymore, but you did live here for a number of years. Do you find, having been someone who grew up in the South and who grew up in a place that is quote unquote “not like this” out here, has impacted… This is not really a well formed question. What I will simply offer is that as someone who grew up in the rural Midwest, I have a lot of really interesting conversations with people out here who make a lot of interesting assumptions.

GC: Yes, they do.

JK: And there are so many people in New York who are not from New York.

GC: But there’s a homogeneousness to it. Sometimes I think for me, like doing events with Boy Erased, what I started to find — and it helped me a lot, actually, with this new book — is I would give a talk and people would come up to talk. Usually a nice older woman. And she would say, I can't imagine ever sending my kid to conversion therapy. I would never do such a thing like that.

At first, I would just say, oh, yeah, of course; thank you for being such a good mother. And now I just go, that's great. I love that for your kids. Also, you do know how brainwashing works? You know how culture works? It depends on where you grow up. And my mom grew up in a 100 person town where there was only one place to meet, which was the Missionary Baptist Church, and she was married at sixteen to my father. So like, yeah, maybe if you were that, you would do it, I think.

JK: Yup.

GC: You’d always listen to what men told you to do your whole fucking life. And then when the man who you're married to — [who] you're supposed to listen to; you're the helpmate — tells you this is what you do, then you think it's a great sacrifice, actually.

I think that as we seek to sort of purify some of society's long ills that we're doing right now, sometimes we can forget that we ourselves are capable of doing all of those things at any moment. Maybe not once you've been shaped a certain way or with a certain education, but we're all capable of it when we're born.

That’s what led to a concept that I call “The Unfathomable” in my work. I think that as we seek to sort of purify some of society's long ills that we're doing right now, sometimes we can forget that we ourselves are capable of doing all of those things at any moment. Maybe not once you've been shaped a certain way or with a certain education, but we're all capable of it when we're born.

I guess that's my little Christian ethic that stays with me. It's the one good thing that stays with me, is all that Jesus-y stuff. And I still believe in that, you know. I don’t pray to Jesus, but I would. Why not? He was a good one to pray to. He wasn't the problem.

I encountered that thought everywhere. And then when I encountered it in myself doing a bunch of events — I would see a young person come up to me, obviously queer or non-binary. And what would come out of their mouth was something I didn't expect, like, thank you so much for writing about God in this way, where you didn't bash religion. I'm still a queer Christian, and I met so many queer Christians on tour, and it really changed my mind on some of my own rigid stances that I developed, and allowed me to kind of pave the way to this new book.

JK: I so appreciate you sharing that, because I wanted to ask you how writing the books has impacted your spiritual journey? But it sounds like that it sounds like Boy Erased paved the way into All The World Beside.

GC: They paved the way for each other, in a way. On a personal level, my dad and I started sharing poetry over the years, just as a way to kind of keep in touch, and I think speak in a language that would allow us to express things without saying them directly. My dad was raised a certain type of man in the South.

JK: A man of a certain age.

GC: And so was I, honestly. I still have hang ups about crying in front of him and things like that because of how I was conditioned. You know, men don't cry. All that bullshit. But I love him deeply, and I think he's a very good person at heart. So we started sharing poetry, and Walt Whitman was one of his favorites, which my gay little heart loved. I was like, you do realize what's in there, dad?

JK: Did he realize what was in there?

GC: He started to. His way of describing it was, he was a weird dude. And I was like, yeah. But like, he said it in an almost appreciative way where it didn't feel like homophobic exactly. It's just slightly Othering. You know there’s a type of othering that you can handle.

JK: Oh, yes.

GC: And we started talking about all these books together, and it was really wonderful because it allowed us to not go down the old pathways that would end in argument. I was in his office one day, and I saw this volume of Jonathan Edwards’s sermons. I was like, what's that doing up there? I didn't know dad was reading 18th century preachers. Cool. Maybe he'll educate himself on where the Baptists got their ideas at some point, because it's all chaotic and random, like no drinking.

JK: American Protestantism is just the wild, wild west.

GC: That’s why it's fun to write about, though. Because you're like, wow, no one's going to believe this shit.

JK: Okay, so Edwards.

GC: So I saw Jonathan Edwards on the shelf, and I started reading more Jonathan Edwards, because I thought, okay, here's another thing to talk about with Dad, and maybe it's a way to kind of reach his — and this is my Aries, right? Maybe it's a way to reach his congregation, because he speaks to like 250 people. If we can change those votes, maybe we can change a few others.

I was just thinking like, okay, what can you do post-Trump? Dad's got a church. Let's try it. And to his great credit, he never asked anyone to vote a certain way and never even hinted at it, thanks to the conversations we had.

JK: That is quite literally doing the Lord's work.

GC: I know! Dad taught me to do it.

I read Jonathan Edwards and fell in love with the language. Of course, much of his theology was odious to me.

JK: It’s disgusting. But it’s pretty.

GC: You read between the lines and you're like, okay, so you went to the “Indian Mission” — there's a lot of colonial dark stuff in there, in between the lines. But that's also what attracted me to him, because I was like, here's this complex person that reminds me of my dad in the past. There are aspects of my main character in this book that remind me of my dad.

I love Foucault, but, like, we fight with daddy, right?

So I used Jonathan Edwards as a starting point and then built from there, [looking] at other preachers at the time. I'll go through all the research if you want, but it was just everything that I could find about sexuality, [and] theory that was based on sexuality that developed through the 18th century. Beyond Foucault who makes me angry half the time. I love Foucault, but, like, we fight with daddy, right?

JK: Oh my god, in your research note at the end of the book called The Unfathomable. It’s so fucking beautiful.

GC: Thank you. It was my favorite part to write.

JK: I loved it. I loved reading that. But when you called him Daddy Foucault, I fucking lost it. I just started snort laughing and [my partner] Meg was like, WHAT are you reading? And I was like, Garrard called him Daddy Foucault!

GC: I feel like there was a slight bit of pushback on that from my editor.

JK: Really?!

GC: There was just a, do you think people will get the humor? And I was like, you know what? If they don’t get the humor, it's going to be fine.

JK: The right people will get the humor.

GC: And the other people who won't — whatever, they'll argue about it, they'll cancel me, I don't care, it's fine. I'm so beyond that.

I got so inspired by the challenge of it all and the, can I write about these queer people without using labels that we know today? How do I do it through the power of suggestion? It was so fun on a craft level.

I don't want to retread too much if you've read the author's note, but I got so inspired by the challenge of it all and the, can I write about these queer people without using labels that we know today? How do I do it through the power of suggestion? It was so fun on a craft level. I mean, it sounds sick to think of it as fun, because these are corollaries to real people who were suffering at the time, in my mind. There were real people that lived that way. But the challenge of writing it was really fun.

JK: I so appreciate that, though, because — and I should say also the 18th century, aside from being personally invested in any book about gay Puritans, for many obvious reasons. *both laughing* The 18th century is so interesting. It was where my graduate work was focused.

GC: Me too!

JK: Wait, what did you do your grad work in?

GC: I was doing it on Charles II, around The Restoration. There was a performance — I have to go back into my grad school brain. There was a performance by this guy named [James] Nokes, I believe, and he was a prominent figure at the time in the court. He mocked Charles II, in a way that was incredibly, like for me, my gay little heart, I was like, that's very queer coded. There’s something weird going on there. And of course, we're still talking about the Earl of Rochester period. So the Libertine was allowed to be a bit more sexually adventurous than other people. So [my work] was around all of that.

I focused pretty heavily on The Fop character in 18th century plays, and how in the 18th century, the Rake and all of those characters transformed into the Fop in the 18th century. That's the moment when things became so much more gay coded, even though they weren't using that word. The Fop, at the very beginning, because of the Rake and Dandy and all those characters, was actually seen as a ladies man who entered their dressing rooms and spoke with them, but then had sex with them. Right? Infiltrating the rooms, like a libertine would do.

But then, it started to become, he's more and more effeminate. He wants to be a woman. So he was labeled as a Sissy. There was no longer any sexual attraction to women. So that was really interesting to me. If I'd gone into queer theory, I would have definitely explored that more. What about you?

JK: Oh, that's so fun. I love knowing that that’s the background.

GC: Yeah, I was obsessed.

So I did have some confidence going in — not complete, because how can you ever know how other people truly spoke and lived? — but I had like an, okay, I think I understand what was happening with sexuality at the time and how people would be very confused internally without any models to see. It’s not like an 18th century colonial preacher is going to know that much about the Fop character that's being staged in London anymore.

So there was this delayed period, where people kind of knew what they were, but they didn't know. They didn't see anything that could affirm that other than sodomy cases and horrible imprisonments and broadsides that would be dispersed. Like, oh look at this sodomy case. It was gossip and scandal.

JK: Yeah. But that was so interesting, though, the way that you were posing those questions — which, of course, coming out of academia. I so appreciated it as someone who is also in ex-academic land, I should say, in terms of the scholarly equivocating that constantly happens around the we can never know. I think in your [author’s note], you're like, you could find a dildo in Abraham Lincoln's bedroom and scholars would be like, oh, we can't know, though! And they wouldn’t be wrong, exactly.

The way that you center that, that's the wrong [way] to be centering our contemporary concerns around essentially recovering and also imagining queer ancestors.

GC: Yeah.

JK: I so appreciate that this is really this imaginal project around queer ancestors into an incredibly painful part of American history.

GC: It’s kind of a weird choice, huh?

JK: No! I think that's what makes it a really healing choice. Not that that’s the point of it. The point of it is that it’s a good story. But at least, I felt that in reading. Because who would imagine queer? — I know I don't when I look at the history of the Puritans. When I was writing about them in my own book, I certainly was not thinking there must have been queer Puritans, but also.

GC: Why would you?! They were such jerks! *both laughing*

JK: They were executing people on Boston Common.

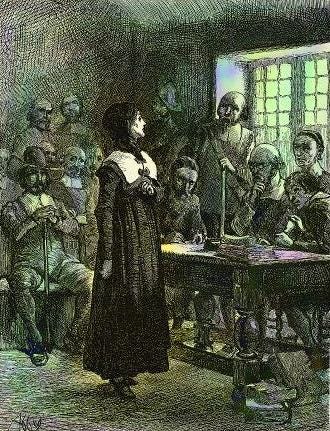

GC: That’s why I kept bringing up the specter of the Salem witch trials [in the book], which were only 40 years before the events in my book. I think what was interesting to me, when I did a lot of research, was seeing how — speaking of heretics, right? Anne Hutchinson was a huge influence for me when I read all about her. I read as much as I could about this woman who was willing to stand up to all of these men and just declare that her interpretation of Scripture was correct. I mean, can you imagine the guts to do that?

That’s who I built Sarah off of, my character Sarah, because I was like, that's who that is, right? Like, talk about Aries.

JK: I was wondering! Because also, in the beginning — and this isn't a spoiler for anyone reading, it’s in the very first chapter, maybe? But [Sarah’s] father calls her and her mom little Anne Hutchinsons.

The writing is also just so good. So good.

GC: That means a lot to me.

JK: I was just reading like motherfucker, this is good.

GC: Good! The jealous “motherfucker” when you’re reading! I needed that from you.

JK: Your use of language —

GC: Well, your use of language is gorgeous in your memoir. You know that.

JK: Thank you.

My 18th century work was a little bit later, the late 18th century, like women's political writing during the French Revolution. And obviously when you're writing historical stuff, you're not trying to recreate it exactly [because that’s not possible], but the way that you wrote it was so readable and also felt so tonally correct.

GC: It took sixteen drafts. So don’t feel like it was easy.

JK: It puts you in the time.

Also, we’ve just been talking, which is the best, but I do actually have some questions for you.

GC: Let’s get into it.

JK: So, it took you sixteen drafts. I did want to ask how the experience — because the subject matter is obviously religion and sexuality, these are central topics to life, obsession, concern. But how was writing the novel different from writing the memoir? Craft wise but also emotionally.

GC: Totally different. The conditions were totally different, too. I was living in Bulgaria at the time [when writing Boy Erased], taking Garth Greenwell's old position at the American College of Sofia, by the way, which is such a fun little moment.

So I was living there and I taught high school full time for three years. During that time, I wrote Boy Erased. So I'd wake up at 4:30 in the morning, write until 7:30, take a shower, go to work, work all day, then do all the stupid extracurricular stuff. Come home at 8 p.m., drink a glass of wine and pass out. That was most of my life during that period, which I could never do now. I was younger then. I just don't have that energy anymore. And so that's one thing that was so different.

But the advantage of that is that with Boy Erased, I was able to section off that often painful writing experience with like, okay, I got to go teach now. I’ve gotta be a teacher and not feel my feelings! Which is not the best way to cope with things. But you gotta do whatever you gotta do to get the book done, you know? *both laughing*

I had tons of support at the time. Lovely friends who would see me at, like 3 p.m. They would see my face that was so dealing with what I'd written that morning, and they'd be like, let's go have a drink and hang out. I felt supported in that little expat community.

But then for [All The World Beside], it took a ton of research, so there were periods of starting and stopping. It wasn't all in my mind. I had to do so much material culture research. At one point, I had pictures of every object that I described in my book, to make sure that I could match it in my brain, so that I wouldn't forget. That’s the green divan that I’m using! It’s a little obsessive. But you know how we do that when we're early on in a project, like you're almost procrastinating? So I did a lot of that.

And it was much more collaborative. I was not used to that. Boy Erased was a very lonely kind of writing experience. And then my editor just approved everything, because it's one of those weird situations where my prose just was pretty much the same from the beginning to the end. I don't know how it happened. I think I waited ten years. I thought about it forever. It just kind of came out, which I never tell my students! Because I'm like, don't believe that. That isn’t how it works!

JK: Sometimes.

GC: Rarely!

This one was so much more collaborative. At one point, I had a completely different style of draft. It was very experimental. It was very all over the place, but a little bit too cold? A little too cerebral. My editor and agent, I wouldn't say went behind my back, but they sort of conspired a little behind my back about how to tell me, okay, we need to embody ourselves in this story a bit more. We need to feel it. We need to get in the senses more. And of course, I knew this. I was teaching nonfiction, being like, please write scenes. Please give us sensory detail and imagery. So it was hard for me to take it in, because I thought I did that. I was trying to do this totally different thing. When I read parts of Justin Torres’ Blackouts, which was recent, I started to think, that's what I was doing a little bit, but he did it better, so I'm glad I didn't do it.

JK: I haven’t read that yet. It’s been recommended to me by so many people.

GC: It’s great. It’s a very different style of narrative; it’s a very cerebral experience, very contemplative.

Whereas All the World Beside, I feel — I hope — is very embodied and rooted in experience. And that's thanks to my agent and my editor pissing me off. I was like *groans*. For a month, I didn't do anything. I was like, I hate their thoughts on this. I think I sent my editor a five page single space, very obnoxious explanation of why queer literature and history is this way. Can you believe that?

JK: I would have done the same thing, honestly. So I feel you on the I’m going to write a paper explaining why this is the way it is, according to queer history!

GC: And she was just totally unfazed. She was like, yep, great. We also need it to be embodied.

JK: How does one recover from that feedback?

GC: One recovers by being an Aries and going, okay, you want that? I'm going to give it to you in spades. You're going to get so much that you're going to have to cut back, right? Which is what happened. I went into so much sensory detail in every scene. And she was like, I don't think we need quite that much.

JK: Overdeliver.

GC: But it's better. I felt so motivated once I had my pity party for a month. I felt so motivated. I was like, I'm going to prove them wrong. I'm going to prove to them that I can be this type of writer. And it was really fun. I love a good challenge. It's scary at first, but I always feel I have to push myself to the exact exhaustion level where I can't do anything more. Or where I'm just so tired of it that I'm like, moving on to the next book! With Boy Erased, I didn't do that. With this one, I pushed myself as far as I could possibly go, and I feel proud of it, even if there's still flaws and things that I can recognize. It's like, okay, I did the best I could at that time and now it's time for a new thing. Books are so weird that way.

JK: So weird. But what you're talking about in terms of the, you push as far as you can go craft wise. How would you describe that sense internally of, I have pushed as much as I can? And there is no more that is going to be wrung from me at this time.

GC: I've only just figured out the way of sensing it, since I've only just now done it. I would say, every time I encountered a question in my mind of, don't you think it's good enough? I thought, no it’s not. I knew that anytime I thought that, it’s not that I couldn’t do it, it’s just that I didn’t want to.

Some of what I did was, I reached out to folks I knew. Garth [Greenwell] is so generous. Whenever I reached out to him and said, can you please read this draft for style? He really did. And he had page numbers with everything that he wanted changed. When Garth tells you a sentence doesn't have the right musicality, you just go with it, right?

I'm going to read every sentence aloud two times, from start to finish, and I'm going to audition every one of them. I'm going to sit there and go, what can be cut? What can be made better?

So enlisting the help of friends was a big one. And then I just got really lucky, because I was scheduled to go to MacDowell [a writers’ residency] in September of last year, and that was when first pass pages came to me. Everyone was so in this deep level of concentration, talking about sentences, that I was like, I'm just going to go to my cabin, and I'm going to read every sentence aloud two times, from start to finish, and I'm going to audition every one of them. I'm going to sit there and go, what can be cut? What can be made better? I did it for three days straight without sleeping. You can only do that at MacDowell or something, where you're just being fed, where food is coming to your door.

I dropped my new project and just thought, I'm going to do the best I can on this last draft. And then when I did, I was like, I'm done.

So I don't know. Maybe the real answer is you just ask other people who are a little further along than you? And you have to trust them. At this point, there are maybe two or three people that I can trust to tell me the real truth at any given time. Those are important people.

JK: Yeah. That's such an important point, though, too, in terms of what you're saying, which connects to what you were talking about earlier with love as being this idea of spirituality, and the sense of community being so important to the creative process. It’s like how you develop intimacy with your own practice, but you also develop intimacy with other people's creativity.

GC: Yeah, you do. You bond through that. And I think pretty quickly you realize who's serious about it and who's not. You know, there are people who are just in it for whatever. But then you meet the really serious people. I'm not saying I'm the most serious writer. I can't wait to play Final Fantasy 7 Rebirth for like five hours today. I procrastinate a lot.

JK: You can have fun and procrastinate and still be very dedicated to your craft.

GC: *laughing* That Protestant mindset!

JK: I’m like, I’m sorry, I’m reading your book right now, it’s very good. This is not written by an unserious writer. I'm going to need you to roll that back, okay?

GC: I need to hear it, because in my brain, I just go, I’m so silly now. I don't have it. I think I'm just exhausted.

JK: You’re in promotion mode.

GC: I fuckin’ hate it. It’s the worst.

JK: Your brain is doing something else right now.

GC: It feels like my ADHD is coming back with a force. It’s really hard for me to be promoting stuff. I'm good at it because I make myself be good at it. I'm not good at it because it comes naturally. You know?

JK: But that's something I feel that doesn't get talked about a lot either. Number one, kind of like you were saying for Boy Erased, you have to be your own publicity machine, like 98% of the time. That's true. But also, it's a skill set, and it’s a skill set you have to cultivate and that you then have to employ. Most people aren't naturally good at it, and even the ones that are don't necessarily want to be doing it.

GC: If it came naturally to just be in capitalism this way, I would worry about myself a little bit. It’s not the best way to shape a human life, I think, being a constant publicity machine just so you can survive.

JK: I did want to ask you — a book about Gay Puritans, which is my reduction, that's me just being incredibly reductionist there because it's actually an incredibly queer inclusive, incredibly queer family. It’s so rich, with all of the relationships. Like it's not just a singular romantic relationship that's the focus, I think, is so important for people who are interested in it to know. There are multiple queer characters, as we would call them, across a multiplicity of familial and found family relationships.

GC: I’m so glad to hear that. That's the thing that gets lost in the marketing. It’s hard to talk about it. I’m actually more interested in Sarah than any — like Sarah and Catherine are my favorites.

JK: It’s so rich. But to your point that marketing this kind of book can happen in this really narrow framework, especially for how publishing is. I wanted to ask how it was selling this book.

GC: Well first of all, I will say I don't ever want to sell anything on proposal again. Never. That was a mistake. I never want to sell anything fiction on proposal again. Because too many cooks in the kitchen early on — it can drive a writer insane.

But to my editor Laura Giuseppe's great credit, she mostly left me alone to try these different things out. I think from the beginning, because publishing is so women-centric, she was into the fact that I was bringing this feminist element to the book.

When I write, I don’t think of feminism or any sort of -ism when writing, because that would be death to the book. But I do think that my early understanding of queerness came from my connection to feminism, because I remember reading Margaret Atwood's essay about the body — it was a very cryptic, strange essay about feminism. I just remember feeling this excitement, like, oh my God, I'm not alone. Other people have been thinking about how women are treated.

I was so close to my mom, you know, I could feel everything that was happening to her in a way. I mean, you're not surprised to hear that from a gay man, but still.

JK: It’s not always true.

GC: This one’s true. I just remember reading that and thinking, oh, life makes sense now. It makes sense why everything's so shitty, because we treated women this way. That, to me, is inextricable from the way that masculinity has been built over the centuries, the way that men have been forced to perform really rigid roles that I think we don't talk enough about.

My trans male friends are always kind of complaining about how they don't get as much media attention because no one wants to talk about men, right? It’s like, shit, you transitioned too well! But it’s interesting because my friends have been conditioned to be female all their lives and then had to fight against that and then figure out what was lovely about masculinity. In that process, I think they've weeded out a lot of the really ugly stuff and made it really beautiful. In my world, trans men would just teach cis men like, oh, you don't have to. You can actually just pick and choose what's good. It’s wonderful to share a moment where your dad helps you shave your face or something. There’s lots of beautiful things that trans men really love about men.

But to me, all of that is predicated upon the release of certain toxic ideas that have been developed in conjunction with the complete subjugation of women. If you're going to do that to a person, it's going to turn you into a monster. And if you're forced to go along with it, you're also a monster. We all are monsters in different ways. The clothes we wear are — you know, we don't have enough money to not buy fast fashion, so we're participating in a really dark and disgusting thing, right? that centuries from now, if people are alive, will say, that's fucked up. They were horrible.

Keeping that in mind, it just felt like this original sin, what we did to women. The royal we.

JK: The “we” on the social and societal level. I think it’s what ultimately shows in so many people's books, regardless of the author's positionality, honestly. Because ultimately, not like you're writing your worldview, but your character and how you feel and think about other people will come through [in a book].

There's a certain type of story that is not apolitical at all, but it has removed the language of politics that we're used to and comfortable with intentionally so that you come to political conclusions yourself [as a reader]. That does not mean that the work is apolitical. It actually means that the work is trying to do a very specific type of politics.

GC: I think that so much gets lost in our very online discussions about this. On a craft level, we get these discussions about how we should write our politics into our stories, which, fine. I agree, that's a certain type of story. But there's also a certain type of story that is not apolitical at all, but it has removed the language of politics that we're used to and comfortable with intentionally so that you come to political conclusions yourself [as a reader]. That does not mean that the work is apolitical. It actually means that the work is trying to do a very specific type of politics.

That is what gets misunderstood with my work all the time. I'm not just writing Iowa Workshop 1950s prose. I am actually doing something that is time honored, that has political ramifications that work because I'm not putting labels on everything.

JK: That was so well said. See, this is the problem! I just want to talk to you!

GC: That’s not a problem. We can just talk anytime.

All the World Beside is available for pre-order everywhere books are sold. You can follow Garrard on all the major social platforms.

ughhh this is such a good interview and i don't read a lot of fiction but I'm very excited for this book!

grateful for this and for y'all.