how to (not) talk to your family about your writing

according to 10 of my writer friends

astrology for writers is an exclusively reader-supported publication. if you enjoy getting this newsletter in your inbox, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

a content warning: this edition contains brief mentions of domestic violence. take care of you.

The holidays are upon us, and with it, for those who visit or host natal family, the inevitable anxiety of discussing, or avoiding, Tender Topics. Such as one’s entire career.

A question arose a while back in the astrology for writers Discord: how do you talk to your family about your writing, especially if you’re writing, uhh, about your family, or events they may recognize? Do you tell them about potential publication in advance? Is it better to ask forgiveness or permission? At the end of the day, do their opinions even matter?

I’ve written (and talked on podcasts) a fair bit about my own experience with writing memoir, and my own ethics therein, over the years. I’ve even taught a now-retired workshop entirely devoted to the topic, Tell It Slant // Uncovering the Truth in Memoir. I’m a bit obsessed with unpacking the central, gnawing tension that so many of us have lived with: not believing we had a right to tell our own stories. Not trusting that we would be believed.

Chalk it up to being a recovering hyper-responsible oldest daughter (and wife) groomed in the evangelical church, a woman who was raised in an abusive home who then proceeded to replicate those upsettingly familiar patterns in her own relationships. I did sometimes misstep and write in anger early in my career, using language and story to lash out at the women I loved who I (then) felt had wronged me. But more often, especially when it came to my own natal family, I often swung to the other extreme, erring on the side of too much caution. Writing into too much tenderness, especially around my childhood, often had me stopping before I’d even begun, absolutely terrified of how my work might impact my parents. Delete delete delete.

For years, the idea of writing anything that could potentially ricochet back onto my mother, especially, kept my jaw locked up tight. Here I was in my thirties, at my desk in my New York City apartment, thousands of miles away, still as dedicated to keeping her secrets, keeping her safe, as I was when I was seven years old, throwing myself in between her and my father over and over, trying to keep his hands off of her.

If I didn’t protect my mother, who would? Wasn’t that my job?

No, my therapist said for years, as I spent months and months and years and years silently eking out a few dozen pages that would become the first draft of Heretic, slowly unclogging the secrets stuffed in my body. No, it was not my job. No, it should never have been my job.

So… what was my job now?

What you believe you owe others, and what you actually owe yourself, is your own journey to discover. But I do believe, from having witnessed many writers (memoirists especially) on their journeys, that writers who are already conscientious of their work’s impact on others tend to be far more self-censoring than the reverse. It’s when someone is not at all concerned about how their work impacts others that there is probably reason to be.

Therapy helps. And time, and distance. But for me, being in community with other writers who were wrestling with similar ethical questions with their own families made all the difference. It made me feel less alone. It showed me that there are many ways to move forward. It reminded me that this is a subject that is dynamic, not static, and that it is subject to change throughout the publication process and even after the book comes out.

And so, I asked some of my dear friends if they would share their experience of talking — or not talking — about writing with their families with all of you.

I hope this offers some medicine as we move into the holiday season.

“Both my mother and my girlfriend's mother wanted to read my novel, and I was happy to oblige. The first thing my mother said was that she ‘learned a lot about lesbian sex.’ My girlfriend's mother noted that it was very gay and maybe not meant for her. I was moved that they wanted to read my work, and it means a lot to me that they took the time to care about what I take the time to do. I've been thinking about these comments a lot, though. My novel is, indeed, pretty gay. I wonder if having all that gay out there in the world over 200 something pages feels, to them, like the limit of what they know and understand, and they think they're being respectful by acknowledging it.” — Natalie Adler, editor at Lux Magazine, whose debut novel Waiting on a Friend was recently acquired at auction by a Big 5

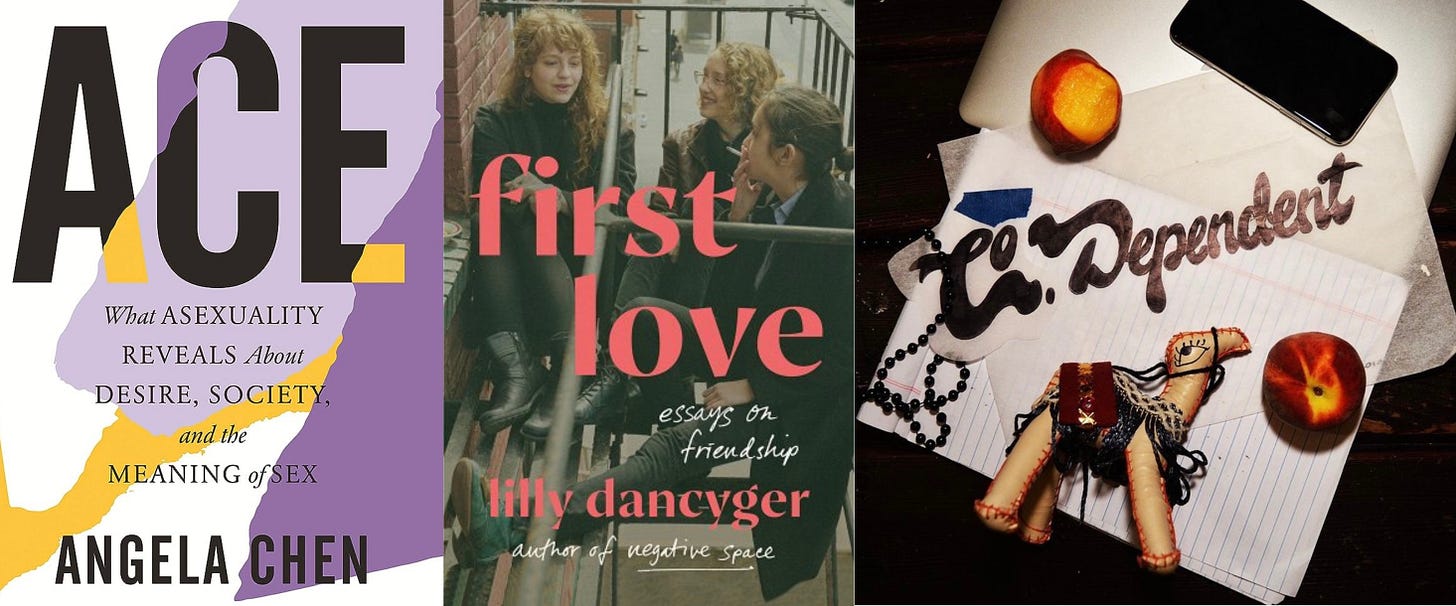

“I didn't tell my parents I was working on a book until I sold the book. I never told them what it was about. To this day we have never, ever discussed its topic or contents. However, I did learn that a nosy relative talked to my parents about the book, so they are aware—but I prefer to live in this world of polite fictions. Such is the Chinese way." — Angela Chen, author of Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex

“I talked to my mom a ton while I was writing my memoir—trying to prepare her for everything I was disclosing, for how I described my upbringing and our relationship, etc. But you can't control how someone will react when they actually read the book, and no amount of forewarning can change that." — Lilly Dancyger, author of Negative Space and First Love: Essays on Friendship (read her Astrology for Writers interview here)

“When I write fiction, I usually do tell my family what I'm working on, but I never let them read anything. With personal essays, though, I never tell them. One time, my mom discovered a personal essay I'd written and published, and she didn't speak to me for over two months. But for me, it was still worth it, and I wouldn't let my family's opinions impact my creative work, even if it does sometimes hurt my relationships with them." — Deena ElGenaidi, creator of the award-winning web series Co.Dependent

“The only people I allow to have any input over what gets published are current partners (and I don't write about my kids, as a rule). In terms of how what I write impacts my family, I will sometimes warn them before something publishes and ask them not to read it or to read it at their own risk (like if I'm writing about my sex life or something). If they choose to engage with it, that's on them and it isn't my job to hold them through it. I am not willing to hold my tongue for other people's comfort and I am careful to always share my story and my experience without trying to speak for anyone else. I know I am probably on the extreme end of the spectrum on this, but I feel strongly in my right to tell my truth!” — Frankie de la Cretaz, co-author of Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League, creator of

(read their Astrology for Writers author interview here!)

“Being estranged from a parent, as I am from my dad, can be as tough as it can be necessary. For me, the distance has been healing because I find that I can write honestly and open-heartedly about our relationship without worrying how he might respond. If I notice that I'm writing from a desire to settle scores, I take a deep breath, look deeper, and start again. (And I always keep the receipts.) My mom and I have a complicated relationship, too, but she's a wonderful storyteller who taught me not to shrink from sharing tough family histories. I interviewed her often as I was writing Ancestor Trouble, and at one point I said that I didn't want to share anything about her life that would be painful for her. She told me to write whatever I wanted, as long as I didn't use her real name.

If you're a writer sitting with or excavating your own difficult experiences of family, I have a few suggestions for you. Be as gentle as possible with yourself. Maintain a commitment to showing up courageously on the page around difficult histories, including histories that implicate you. And always remember that writing about abuse is not abuse.” — Maud Newton, author of Ancestor Trouble: A Reckoning and a Reconciliation (read her Astrology for Writers author interview here!)

“I don't usually ask permission, but I do try to write from a place that's true to my experience but not actively trying to hurt other people, including my family. The essay about a boy getting into bed naked with my father by accident at like 5am on Father's Day morning – I know – actually facilitated a hard convo between me and my dad. It was a good thing! He even came to a reading in Portland where I read it out loud, in public. The essay is now offline because Gawker sucks balls and not in the fun way, but you can find it on the way back machine.

[That said], I wish my parents didn't read some of my work – like in INSIDE/OUT when I wrote about douching and messy butt sex lolsob – but I can't stop them, either. It can be awkward, but it's part of being a writer, I think, and writing about the messy queer bits that are too often hidden.” — Joseph Osmundson, author of INSIDE/OUT and Virology: Essays for the Living, the Dead, and the Small Things in Between

Speaking to my family about my writing has been an interesting experience. For one, a large contingent of my family is not particularly fluent in English, and neither of my books have been translated into Chinese, so people such as my mother have gone to length such as plugging in the text to Google translate and trying to interpret it that way.

In terms of speaking to them about particular things that I want to write that are close to their lives, and may include details of our lives together, I’ve generally gone by my intuition. I’m mostly thinking about my spouse and my mother, who are the main people that I write about in my personal nonfiction. At one point, I asked my mother if she would be OK with me writing about something that I felt she might not be comfortable with being made public, and when she said that she was, indeed, not amenable to my writing about that topic, I fully listened to her. After all, I find very little point in asking if I’m not going to take the answer into serious account.

For my next nonfiction book, this will become trickier. There are extended family members who are very sensitive to being written about, even if I plan to write about them in the most delicate way possible—and yet I can’t imagine writing what I want to write without including that material. I’ll have to figure it out at that point, but it’s boiling in the back of my mind already. I have friends who have been ostracized from their families and communities at large; these questions are not superficial ones, and I’m glad that we’re having these conversations as writers to see what we can make of these complex situations. — Esmé Weijun Wang, author of The Border of Paradise and The Collected Schizophrenias: Essays, creator of

"When I first started writing, I didn't tell anyone anything about what to expect. If I'm being honest, I didn't think anyone would read it. When they did, there were a couple of hard conversations — one with my mom whose memory is failing. That came down to my word against hers, and we still struggle if my writing comes up. That being said, my family's opinion has not altered my creative process. I was very affected by Melissa Febos’ Body Work, which states that cruelty rarely makes for good writing. That's been the bar I've set for myself since those first couple of books. If it's true but compassionate and important to my story, I just deal with any fallout. If it seems cruel or unnecessary, it gets cut. While I feel in my waking life like that came more from a need to be a better writer, I do think I might be a little overcautious in terms of what the line is because of my family." — Cassandra Snow, author of Queering the Tarot and Queering Your Craft and co-author of Lessons from the Empress (read their Astrology for Writers author interview here!)

“Once upon a time, my family's opinions on my work, career choices, and creativity was incredibly important. But the older I've gotten, and the more I've built community that is in line with my own values, identity, and dreams, the less I've worried about what my natal family might think — and the more I've focused on supporting my chosen family instead. My parents know that I've written a book, though I've never told them the title or details beyond the fact that it's about tarot. And I have included anecdotes from my childhood and stories about my parents in personal essays and pieces on my newsletter over the years, but I have absolutely no idea if they've read those things. If they have a copy of my book, they've never mentioned it. They have, however, mentioned that they've read Jeanna's book Heretic. It's entirely possible that my parents know how I fuck, but not how I pray. Such is being an estranged, queer, witchy eldest child.” — Meg Jones Wall, author of Finding the Fool: A Tarot Journey to Radical Transformation (read their Astrology for Writers author interview here!)

Many, many unending thanks to these incredible writers for sharing their personal journeys here with all of us. Please go read and buy their incredible books, follow them on socials, take their classes, all the things.

And to you, dear writers, whether you are seeing natal family anytime soon or not, whether you are on speaking terms or are estranged — know that you are not alone in your quest to parse the truth, and to tell your truth.

That there are ways forward through this morass that can respect the depths of others’ stories while still honoring the reality of what happened to you. That there are others out there who will absolutely believe you, and affirm you, even when those closest to you would, perhaps, rather you were shut up in silence.

You’ve got this.

Thank you for reading this edition of astrology for writers. If you enjoyed it, please consider becoming a paid subscriber, or sharing on social media or with your writer friends.

also also also. a reminder that ~early bird pricing~ for the next session of showing up to the work, which will run for 2 hours a day, 3 days a week between january 3-march 21 of 2024, expires this friday, 11/24. hope to see you there!

“It's entirely possible that my parents know how I fuck, but not how I pray.” Don’t mind me, just crying over the weight of this (deeply relatable) tiny poem 😭

The first time I sold a story, I was OVER THE MOON. But as soon as my mother found out it was erotica she passed judgement and ceased being excited with me, I clammed up and never spoke of it again. She is immensely anti-sex (due to traumatic events in her own life and religion). To this day, I never talk about my writing career with family—save with my little sister.